The Central Pacific and Union Pacific railroads met at Promontory Summit in the Utah Territory in May 1869/Andrew J. Russell

The Frenzied Completion Of The Transcontinental Railroad In Utah

By Kurt Repanshek

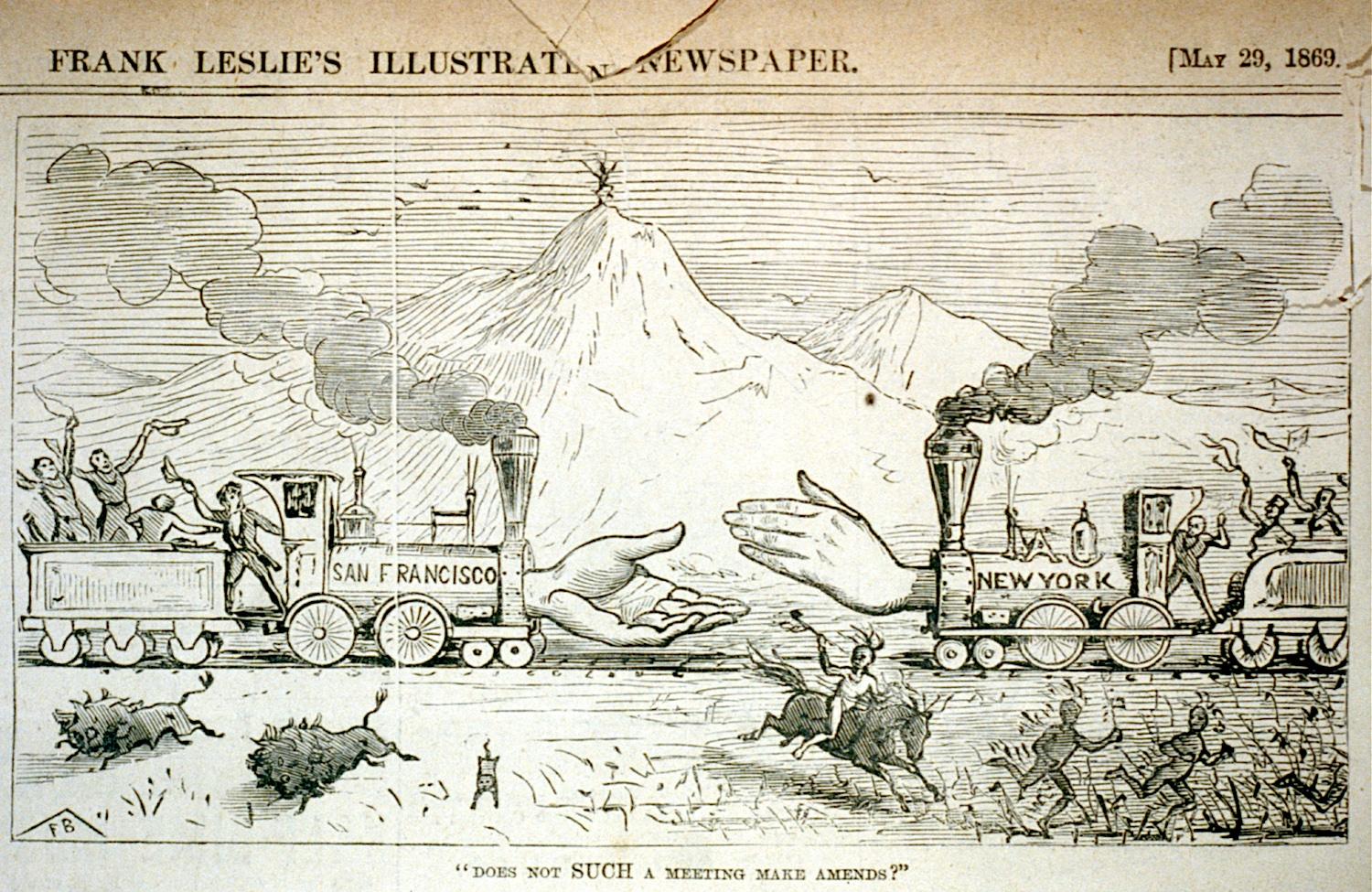

Despite the iconic image of the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad that was sealed with a golden spike hammered into a laurel railroad tie, the closing weeks of the engineering feat were frenzied.

Hundreds of groups of men recruited from families and Utah communities by Latter-day Saints leader Brigham Young took to the surveyed track lines that climbed up to Promontory Summit on the northern tip of the Great Salt Lake with wheelbarrows, shovels, and scrapers to gouge the railroad grade that Chinese and Irish workers would follow with the ties and tracks needed to bring the Central Pacific and Union Pacific railroads together. While maps completed by engineers were to guide the work, they were challenging to follow out in the field.

“As they followed the survey stakes through to their camp at Blue Creek, they noticed the location maps did not follow the stakes on the ground and the various lines crossed each other several times,” National Park Service historians noted in documenting the final weeks of the railroad’s completion. “On the Promontory Summit, [Brevet Major General G. K. Warren, a government commissioner sent to inspect the work in March 1879] was not exactly sure where the two lines would be built.”

Still, the entire project was an engineering feat. During the course of the work, according to the Park Service, “[T]he Central Pacific laid 690 miles of track; the Union Pacific 1,086. They had crossed 1,776 miles of desert, rivers, and mountains to bind together East and West.” Along the way the Central Pacific used explosives to create 15 tunnels through the Sierra and built “37 miles of peaked snow sheds and sloped galleries to keep snow off the tracks.”

Often-lawless tent towns popped up along the final miles of the route with saloons, restaurants, dry goods, and more to cater to the railroad crews, while land speculators bought up parcels they believed would profit them from the “Junction City” that would arise from the railroad’s completion. As the grading work continued and engineering changes were brought up, crews crawled across the landscape from the east and the west and the tent towns moved with them.

“The companies are running a race side by side. But where will they meet? That’s the question,” read a story in the Salt Lake City Telegraph newspaper. “The Ogdenites seem to know it; then the New Bear Riverites are quite confident that they are building at the right place; then again the Junctionites, on Blue Creek, will bet anything they have struck it.”

Yet as late as April 1869 there was no agreement guiding where the two rail lines — the one the Central Pacific RR had pushed across the Sierra and the other the Union Pacific laid over the Plains from Omaha — would meet. Even that agreement reached early April was fluid.

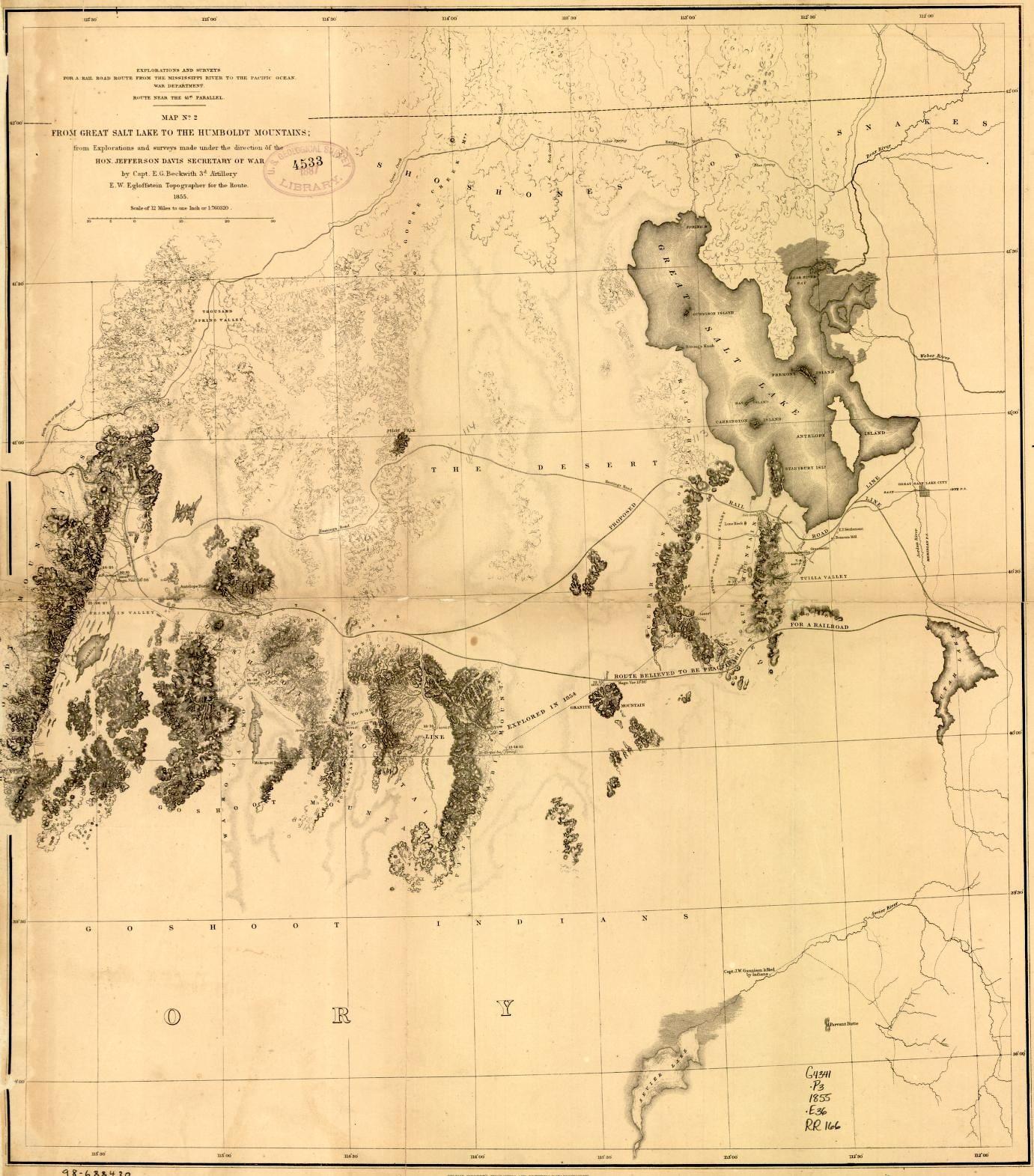

“The place where the two roads shall meet and connect shall be at some point within eight miles of Ogden [Utah],” read the agreement hammered out between the two railroads in Washington, D.C., on April 9 and approved by Congress the next day. In its resolution formalizing the agreement, Congress identified Promontory Summit [not Promontory Point, as some newspapers of the day wrote] as the point for the meeting of the rails. It was a location that differed greatly from a survey the U.S. Army conducted in 1855 to identify a rail line from the Mississippi River to the West Coast. That route passed to the south of the Great Salt Lake.

Because the railroads were paid for miles of track laid, survey teams for the two actually passed each other, and parallel tracks were laid at the summit.

But the final word from Washington, D.C., on the meeting point spawned the pitching, almost overnight, of a tent city of speculators at the summit. Their hopes no doubt were crushed when the Central Pacific opted to make Ogden its central junction for the region.

Explaining The History

That history, and more of the Transcontinental Railroad, is explained today at Golden Spike National Historical Park at Promontory Summit, a sagebrush-strewn landscape that looks extremely close to the setting the railroad workers and speculators found in 1869, minus the tents and telegraph lines that had wires extending to both the ceremonial golden spike and the silver maul. Once the maul struck the spike to drive it into that laurel tie, it would make the connection and send word across the country of the historic moment.

Inside the engine house I caught up with Cole Chisam, the park ranger who not only is the engineer who drives the two steam locomotives housed at Golden Spike but is a resident railroad historian.

“This is pretty much what you would have seen in the 1860s. It’s built within a quarter of an inch of accuracy, size-wise,” Chisman said as we stood in front of the gleaming red, blue, and golden Jupiter, a modern-day brassy replica of the original wood-fired Central Pacific locomotive that crossed the West to meet the UP’s No. 119 at Promontory Summit. “The colors are as accurate as we can possibly get to at this point. All the brass you see is what you would have seen back then. All this stuff here that looks like gold paint is actually 23 karat gold leafing. So it’s essentially what you would have seen.

“Back then it was the Gilded Age in the United States. Most people know it know it as the Victorian era. If you had the money, you showed off that you had the money,” he continued. “But it was also a form of advertisement for the railroad. The United States had so much immigration at that time, and literacy rates weren’t that great. Finding a common language in which to advertise your company was kind of difficult. But everyone understands bright colors and shiny objects. And much like a fishing lure, it would attract the eye. And in theory, if your engine would look better than your competitors, you might get more ticket sales than your competitor.”

While Chisam tossed some logs in the locomotive’s firebox to bring up the steam pressure needed to power Jupiter, his crew focused on polishing the many brass railings and fittings on the locomotive and oiling its wheel bearings and other moving parts.

“Prep work starts for us at 8 a.m.,” he explained. “We have to light the fire — it’s going to take a while for the steam locomotive to build up pressure. When we’ve run the day before, it only takes us about an hour-and-a-half, an hour-and-45 minutes, to get her back up to operating pressure of about 140 pounds. Then we can take her out of the shop. But in the meantime, it’s going to take a while to build up that pressure. So you’re constantly checking the fire. But also, this machine has a lot of moving parts that have to be lubricated and oiled, so you’ll probably see some of the firemen around today, that are going around oiling all those points to make sure they’re lubricated, so when we pull out of here, everything moves nice and smooth.”

Chisam explained that the Jupiter burned wood, not coal, because it was readily available. Coal would have had to be shipped from the East Coast around South America to California, or taken by wagon across the country, while wood was in constant supply as the surveyers and graders opened a path across the Sierra for the tracks.

“So what the Central Pacific would do was set up lumber mills and then mill their ties, and then whatever was left over you could burn in your engines,” he said.

Getting coal to No. 119 was much simpler, as the Union Pacific’s tracks stretched to the East Coast.

Whether coal or wood, the fuel was used to generate the steam needed to power the locomotives.

“There are approximately 800 gallons of water in the boiler of the locomotive and an additional 2,000 gallons of water in the tender,” said Chisam. “The boiler’s water level would drop during operation from producing steam and the 2,000 gallons in the tender would be pumped or injected into the boiler as needed to maintain an appropriate level of water. The water in the boiler, aside from producing steam, also acted as a water jacket around the firebox and firetubes, keeping them from weakening under the heat of the fire, which is part of the reason maintaining the water level in the boiler is so critical. When they would start to run low on water in the tender they would stop at a water tower to fill the tender back up.”

Where would Jupiter find water as track was laid across the Sierra?

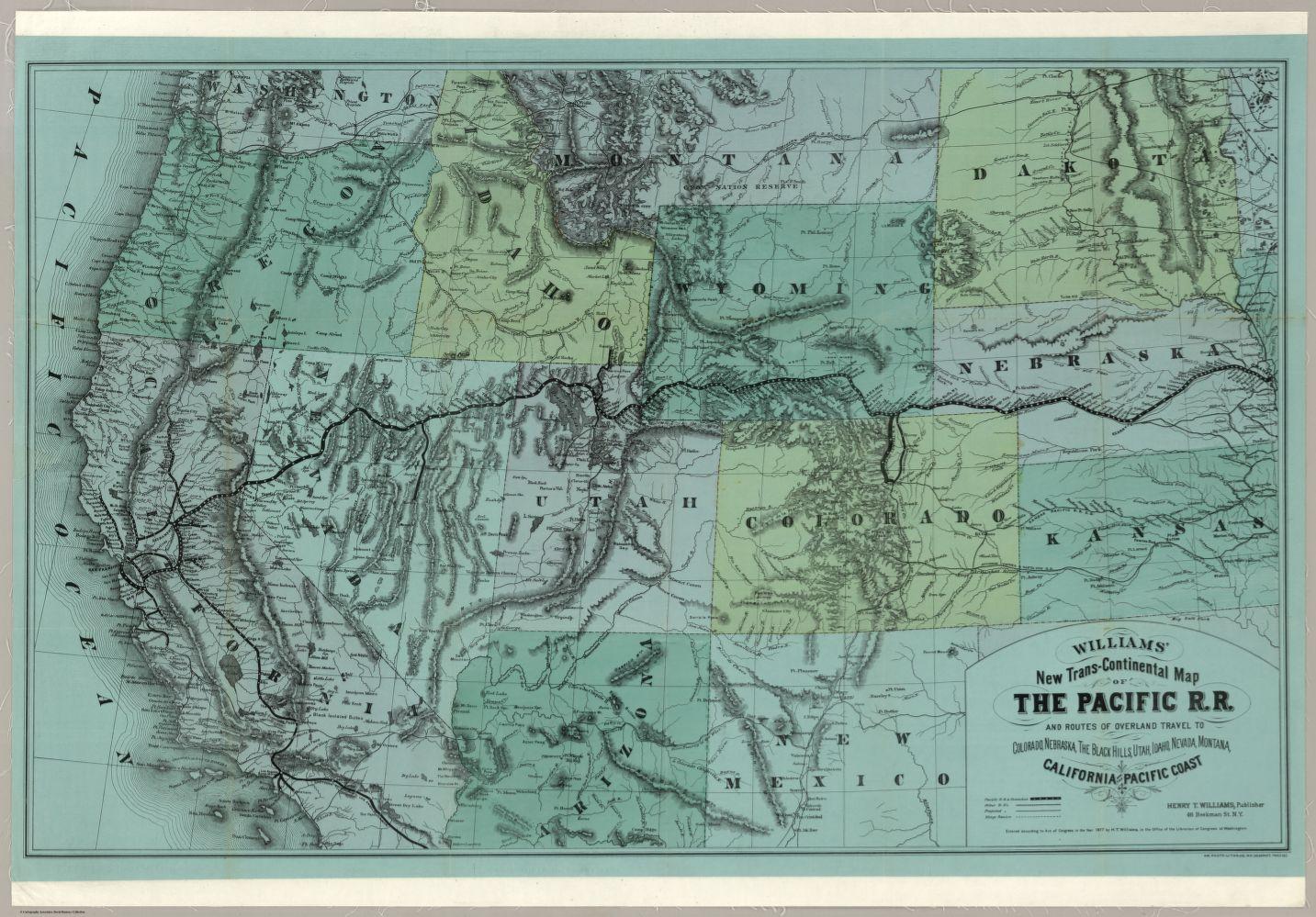

“The survey parties would look to find the route with the flattest grade with access to fresh water and then incorporate stations, water towers, and other support buildings as they went,” explained the ranger. “This is the primary reason why the Union Pacific followed the Platte River through Nebraska and the Central Pacific followed the Humboldt River through Nevada. In fact, the impact of where the railroad put down stations can still be seen today along much of the original route (I-80 corridor) from Nebraska to California. Water availability was the primary reason that the Promontory route with its steeper grade was chosen over going south of the Great Salt Lake and connecting with Salt Lake City. In some cases where no water sources could be obtained, the Central Pacific would ship water out to stations on flat cars with water tanks on them to supply that location. If they were located in more of a flatland environment, the easiest method of getting water into the water towers was through mechanical pumps, often driven by windmills. If located in more hill country, depending on if the water source was located above the route, they could use gravity and build structures to divert some of the water from that source to fill in the tank instead.”

An 1855 survey by the U.S. Army proposed running the railroad south of the Great Salt Lake/Library of Congress

Henry T. Williams’ map was printed 8 years after the completion of the transcontinental railroad. The original railroad names hundreds of stops along the tracks noting major and minor stations by font size. Branches off the main trunk line are shown from Cheyenne to Denver, from Palisade to Eureka (Nevada), and throughout California north to Redding, Oroville, Calistoga, and Clovendale, and south to Soledad, Fremonts Pass, and finally to Los Angeles, San Pedro, and Anaheim. Other railroads in use include the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe, the Denver and Rio Grande, and the Kansas Pacific. The Northern Pacific has yet to be built although a proposed route is shown. It was completed in 1883. Stage routes connect to the railroad across the west allowing for movement of goods and people throughout the entire region/Stanford University

A Coincidental Meeting

The two steam locomotives that met head-on at Promontory Summit in the Utah Territory on May 10, 1869, were never supposed to be there in starring roles.

The Jupiter was owned by the Central Pacific Railroad. It had been built in 1868 by the Schenectady Locomotive Works of New York state. It was known as a 4-4-0 locomotive, the description based on the number of wheels it had: four wheels on the leading ‘truck’of wheels, and four driving wheels. Since there were no trailing wheels, the zero was tagged onto the end. It was also one of five locomotives built to the same specifications for the Central Pacific Railroad. The others were named the Storm, Whirlwind, Leviathan, and Gazelle. After being built, they were then dismantled and transported to the West Coast via ocean-going freighter.

The Union Pacific’s No. 119 (no fancy name, just 119) also was a 4-4-0 configuration steam engine, but it was fueled by coal. It was built by the Rogers Locomotive and Machine Works of Paterson, New Jersey, in 1868, along with four other locomotives numbered 116, 117, 118 and 120. Once the 119 was placed into service, it was kept busy hauling coal from Rawlins, Wyoming, to Ogden in Utah.

According to the National Park Service, Central Pacific President Leland Stanford had selected the Antelope to haul his special car to the celebratory event. En route to Promontory Summit, the “Stanford Special” followed a passenger train carrying sightseers to the “wedding of the rails.” As that train passed through a large mountain cut still being cleared, workmen there did not notice a small green flag flying from the locomotive, a flag indicating that another train followed close behind. Immediately after the first train passed, workmen rolled a huge log down the cut, according to a Park Service account. Around the corner came Stanford’s Special, and the Antelope struck the log. Park Service historians say the Antelope wasn’t derailed but was so badly damaged that Stanford’s cars were coupled to the other train’s locomotive, the Jupiter.

No. 119 also wasn’t intended to be at the crowning glory of the Transcontinental Railroad’s completion. It seems that the train hauling Union Pacific Vice President Thomas Durant to the event was stranded at Devils Gate in Weber Canyon, a narrow river gorge east of Ogden, when storm waters washed away some of the supports of a bridge across the Weber River. While the locomotive was able to give passenger cars a nudge to cross the bridge, the engineer thought the locomotive was too heavy to ride the rails across it. As a result, a call went out to the station in Ogden, and the No. 119 was sent to pick up the passenger cars and Durant and take them the rest of the way to Promontory Summit.

While neither engine survived — Jupiter was sold for scrap in 1901, and No. 119 met a similar fate not too many years later — in 1975, O’Connor Engineering Laboratories of Costa Mesa, California, agreed to build replicas of the two locomotives. With no plans or blueprints, engineers and technicians used a locomotive design engineer’s handbook from 1870 and scalings of enlarged 1869 photographs of the locomotives to construct the locomotives you see today at Golden Spike National Historical Park.

Never A Down Moment

Keeping the two steam engines in working condition is a year-round project. During the annual year-end Steam Festival the locomotives would take turns putting on the steamy exhibitions; while the Jupiter put on the show this past December, No. 119 was being dismantled for maintenance work. The engine’s cab had been removed so it could be sanded down to bare wood and restained, and the running boards were going through the same process. And then there’s the brass.

“This is one solid cast piece of brass that comes off every year and gets repolished,” said Chisam, pointing to a brass railing that stretched the length of Jupiter. “A lot of it seems cosmetic, but a lot of parts we have to take off to get to other things. …When both engines were here in 1869, they were essentially brand new. The 119 had been in service since November of 1868. I think Jupiter was in service as early as February of 1869. So they were relatively brand new. And engineers and firemen were typically assigned to an engine, so much like firemen today at a firehouse, they are always waxing their engines, and it was the same thing back then. It was their engine, so they took pride in it. So because of that, every year when we have [the] May 10 [celebration], they gotta look their best.”

While the Jupiter was sparkling, the same couldn’t be said of No. 119 because of its state of dismantling.

“It’s almost like a giant puzzle every year, that you got to make sure you put it back together in the right order and get the things ready to go back on in the right order,” said Chisam.

While the park’s crews can handle the staining and painting, when the gold leaf on either locomotive needs some brightening up, an expert is summoned to apply new leaf.

While the annual Steam Festival is the main event of the year at the park, you can see the locomotives operating daily from May 1st through Columbus Day October 14th, except on days when they are scheduled for maintenance.

Daily Locomotive Ranger Programs:

10 a.m. — Arrival of the Jupiter

10:30 a.m. — Arrival of the No. 119

1 p.m. — Demonstration run with both locomotives

4 p.m. — Departure of No. 119

4:30 p.m — Departure of Jupiter