Seventy-five million years ago, the landscape was a warm, shallow inland see at what is now Badlands National Park / Rebecca Latson

Fossil Hunting With The Rangers At Badlands National Park

Words and Photos by Rebecca Latson

Editor’s note: It’s illegal to collect fossils in Badlands National Park, or any other park, for that matter, without a permit. Rebecca Latson during her recent visit to the park was given a tour of its fossilized landscape by Ranger Edward Welsh and Interpretive Ranger and Geoscientist Mattison Shreero.

Badlands National Park in South Dakota is a treasure trove of fossils. Walk in any direction and you may find a fossil bone shard or tooth or seed or even a dung beetle ball (yes, seriously). If you are really lucky, you might even discover a fossil skull.

As you wander around the park’s landscape, it may be difficult to envision the crumbly sandstone, siltstone, and limestone covered by a warm, shallow sea some 75 million years ago. Fast forward to about 30 million years ago and a semi-tropical environment of grasslands and open forest replaced the now-drained sea. These environments, millions of years apart, created habitats for a plethora of life that ultimately left behind fossil calling cards — proof of their existence at what is now Badlands. Visitors, rangers, and scientists have discovered a variety of fossils from baculites (squid-like creatures), to mosasaurs (gigantic marine finned lizards with very sharp teeth), to mammals such as Oreodonts (sheeplike animals), Hoplophoneus (a leopard-sized saber-tooth cat), and the recently-discovered housecat-sized deer Santuccimeryx elissae.

Fossil hunting is a fun pastime in the park, but how do you identify something as a fossil out there, and what should you do if you find a fossil?

Last month I spent an hour at Ben Reifel Visitor Center’s Paleontological Laboratory (typically open June – September) with Badlands Education Specialist Edward Welsh and Interpretive Ranger and Geoscientist Mattison Shreero as they proudly showed me the newly-named Santuccimeryx elissae deer skull and discussed its importance.

Santuccimeryx elissae skull and its 3-D copy, Badlands National Park / Rebecca Latson

We then drove to an area not too far from the visitor center and spent another hour roaming the landscape while Welsh and Shreero discussed the importance of how fossils flesh out the geological and paleontological history of Badlands. Before looking for fossils in earnest, Welsh set the geological story with a little “arm wave geology” introduction.

Leptauchenia Beds, Badlands National Park / Rebecca Latson

In the image above, you see a Badlands landform with different-colored layers of sediments. Beginning at the bottom, there’s a buff brown-reddish layer, then a thin white band, then a thicker gray band, then another white band of sediments. Between those two white bands is the fossiliferous zone in which we would be searching. The old name given to that zone is the Leptauchenia Beds, so named after a tiny, short-faced oreodont. Other appellations for this same zone are the Bjork Siltstone (named after Phil Bjork, a professor of the South Dakota School of Mines and Technology who heavily collected within the area), and Unit Eight of the Poleslide Member of the Brule Formation. Typically, it’s just called the Leptauchenia Beds.

“Everything comes out of that,” Welsh told me. “This zone is the sweet spot where the fossils are pouring out — wherever that layer is exposed, fossils are common.”

With that in mind, we set off, two keen pairs of eyes and my novice eyes scanning the light tan gravel, blindingly bright in the mid-morning sunshine. To me, everything looked alike. It took the better part of 30 minutes to finally distinguish fossil from gravel as I trained myself to be a “fossil bloodhound” under the guidance of the two rangers.

Edward Welsh and Mattison Shreero, Badlands rangers in their element, Badlands National Park / Rebecca Latson

A fossil hackberry seed, Badlands National Park / Rebecca Latson

“Aha! A hackberry fossil!” Looking up from my thus-far fruitless search, I saw a tiny white seed nestled in the palm of Shreero’s hand. How she found that miniscule (3-4 mm) fossil among the same-hued gravel I’ll never know. But yes, I was looking at a fossil hackberry seed. Welsh told me “[hackberry is the] only plant we get in the fossil record [here]. Most often, if an area is good at fossilizing animals, it’s not so much at fossilizing plants, or vice versa.” In addition to tiny hackberry seeds, the sharp-eyed rangers discovered root casts, trace fossil burrows, and fossil dung beetle balls.

Say what? A dung beetle ball?

A fossil dung beetle ball, Badlands National Park / Rebecca Latson

This image of a stone sphere about an inch in diameter is an ancient dung beetle ball, considered a trace fossil because it is evidence of a particular life form but not the actual life form itself. Because of their smoothly-spherical shape, a dung beetle ball was one of the first fossils I eventually found (yay me). Welsh told me to look closely at that dung beetle ball and perhaps I’d see bits of ancient vegetative matter incorporated into that stony sphere of poop.

Fossil bones took a bit longer for me to identify. “Typically, there is red staining that shows up when the fossil comes into contact with the rock. Blood red — don’t ignore that. Sometimes bone is a little yellowish and sometimes it’s white like the rock,” explained Welsh, who also told me if I found a fossil with a very porous appearance, like what I’d see looking at a bone in cross-section, I should try touching my tongue to it and see if it sticks to my tongue, in which case, that probably was also fossil bone.

Fossil bone, Badlands National Park / Rebecca Latson

Fossil bone, Badlands National Park / Rebecca Latson

Fossil bone with the author’s mini-recorder for scale, Badlands National Park / Rebecca Latson

Fossil teeth, on the other hand, will be dark, the rangers informed me. Teeth are a very important find because they help identify the animal. Ankle bones are also great identifiers.

“With mammals, you typically need their teeth to help identify, or some other part of the anatomy that really stands out. Sometimes [fossil] ankle bones help [identify an animal] because it tells something about the animal’s locomotion, lifestyle, and habits. If you are an even-toed hoof mammal [for example], there is a bone called the astragalus. It’s the hinge on the tibia — the bone that connects the end of the tibia. It has a double pulley setup that only those animals have. This bone is so diagnostic that it’s used to identify certain mammals,” said Welsh.

For a bit of trivia, he threw in that Romans used the sheep astragali as dice for their games.

Fossil oreodont tooth, Badlands National Park / Rebecca Latson

Normally, what a fossil hunter might find are small bone pieces.

“Fossil bone is very fragmented and busted up. Once in a while, you might come across something that is ‘grinning at you.’ You’ll find fossils in river channels from the very top of the formations,” which in prehistoric times were in the low areas with water flowing through them. “So when you look upwards and see an ancient river channel, that is where the river was flowing … This is where Vince Santucci did his work, heading up these channels and finding out what is in them,” Welsh told me while keeping his eyes glued to the crumbly rock around him.

Santucci, whose name was attached to the park’s latest fossil find, that of a small hornless deer, is the National Park Service’s senior paleontologist. Early in his career he was stationed at Badlands.

In addition to that dung beetle ball find, under the tutelage of the two rangers I began to differentiate the bits and pieces of bone from the surrounding gravel. Once you know what to look for, fossils practically pop out everywhere.

Ok, so what should a park visitor do if they discover a fossil? Don’t take it with you! Yes, the urge to collect and take home your fossil prize from Badlands National Park is quite tempting, but just don’t do it. Aside from the fact that units within the National Park System prohibit the collecting of fossils, artifacts, rocks, and minerals (i.e. it’s illegal), removing a fossil from its natural resting place takes away vital information useful to scientists studying the geology, paleontology, and ancient environment of the local area and the park as a whole.

Shreero told me if someone finds a fossil, they should do three things:

- Leave the fossil exactly where it was found

- Take photos and get GPS coordinates

- Report it in person or email their finds to the park

Welsh added one should also take a close look around that fossil find. Bone shards littering the area may indicate something falling apart from elsewhere. Follow the path up to see if anything is eroding out and include that information in your report to the park.

I asked if fossil finds reported by visitors were usually larger sized and Shreero said yes, most of the times the find will be larger or identifiable, but sometimes they receive an email about something “small and subtle and amazing that ultimately leads to something else. We get lots of visitor site reports,” she said. “An important part of that paleo lab at the visitor center is that they can engage the public directly and they can see the work being done and how much care is being taken on the resource and they [the public] become invested in it themselves and can be taught exactly how to do the right thing if and when they find fossils. The park encourages ‘stewardship through participation’ [aka Citizen Science].”

Talking about fossils with a hiker, Badlands National Park / Rebecca Latson

Speaking of stewardship through participation, if you see suspicious activity like a poacher digging into the ground or removing a fossil from the area, report this to the park immediately. Badlands National Park takes theft seriously.

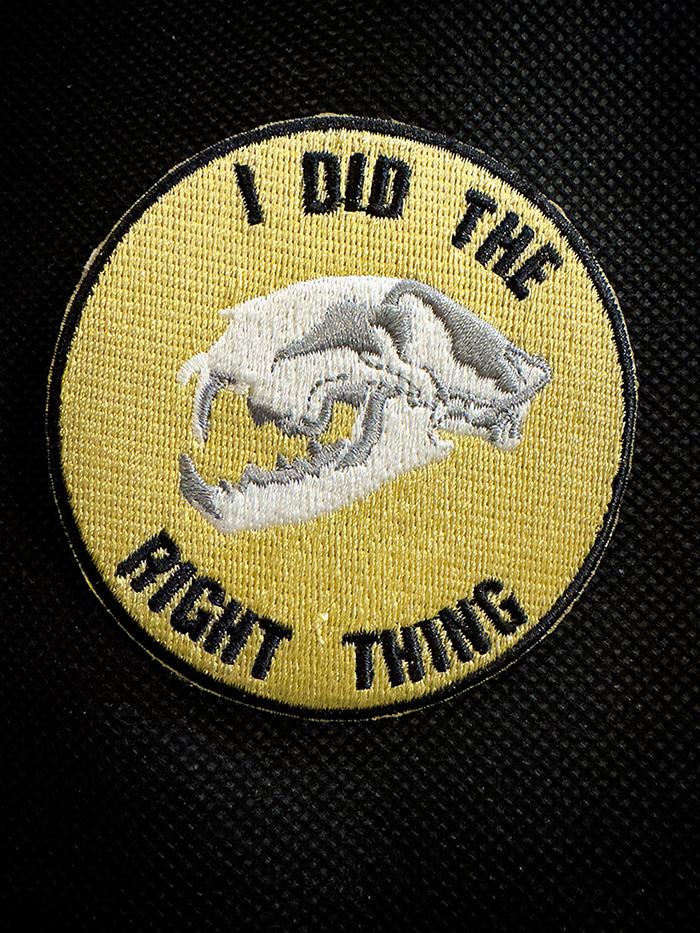

My morning with the fossil-finding rangers was a blast and I was rewarded with a Fossil Finder Patch back at the visitor center. If you visit Badlands National Park, find a fossil, and do the right thing by reporting it, then you deserve a Fossil Finder Patch, too, don’t you think?

Do the right thing when you find a fossil at Badlands National Park / Rebecca Latson