Yellowstone National Park’s unique and pristine environment each year lures millions of tourists who are responsible for generating nearly 2.3 billion pounds of carbon dioxide emissions, according to a new study/Rebecca Latson file

Tourism to Yellowstone National Park, which attracts millions of visitors a year searching for spectacular scenery, geothermal wonders, and a pristine environment, is responsible for generating nearly 2.3 billion pounds of carbon dioxide emissions each year, a new study says.

It’s a staggering output of a greenhouse gas that is a major contributor to climate change, one that the study’s authors hope will prompt the tourism industry to develop “strategies to reduce emissions and hasten the achievement of global carbon dioxide (CO2) emission reduction targets.”

The authors, Emily J. Wilkins of the U.S. Geological Survey, Jordan Smith from the Institute of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism at Utah State University, and Dani T. Dagan from Department of Parks, Recreation and Tourism Management, Clemson University, focused on Yellowstone because of its global prominence.

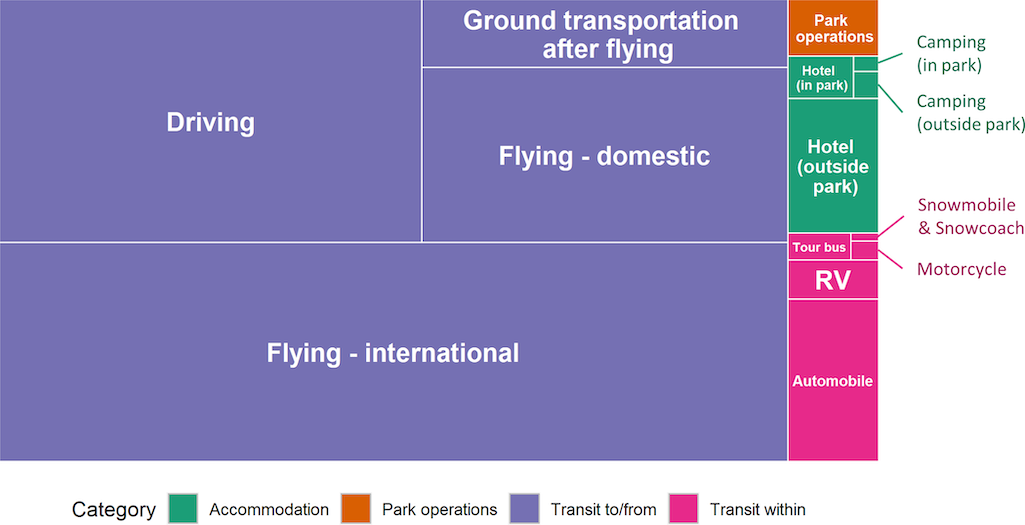

What they found was that of that annual CO2 output, the bulk is created by visitors heading to and leaving the park [roughly 90 percent]. Inside the park, transit is responsible for about 5 percent of the total, with lodgings accounting for 4 percent, and other park operations generating about 1 percent of the total, stated the study, which appeared on PLOS Climate last week.

Air travel by visitors heading to Yellowstone National Park is the largest generator of CO2 emissions, according to the study/PLOS Climate

“Nature-based tourism provides numerous personal and social benefits to tourists; it also plays an essential role in the economies of many municipalities, counties, states, and even countries. This is certainly true in the western United States, where many state governments actively promote outdoor recreation and tourism at national parks and other public lands to out-of-state and out-of-country markets,” the authors wrote. “However, focusing primarily on the social and economic benefits of tourism obfuscates the many environmental costs of tourism. Principal amongst these effects are CO2 emissions, for which tourism contributes 8 percent globally.”

The study calculated that “[V]isitors who fly [to reach Yellowstone] only made up about 35 percent of all visitors, but produced 72 percent of the emissions related to transit to and from the park.”

Inside the park, recreation vehicles generated the highest CO2 output per person, they found, at 70.07 kilograms [154.5 popunds], “while tour buses had the lowest CO2 emissions per visitor (15.46 kg) [34 pounds]. Only 6 percent of visitors travel by RV within the park, yet these visitors produce 17.2 percent of all emissions related to transit within the park.”

Tourism to Yellowstone National Park generates more than 2.2 billion pounds of carbon dioxide emissions annually/PLOS Climate

The problem is only expected to get worse in the coming years, the authors added.

“By 2035, tourism-related emissions are expected to grow by 161 percent from 2005 levels, largely due to a projected growth in air travel and longer transit distances,” they wrote. “Although the overall efficiency of transit has increased over time (i.e., increasing km/L of vehicles), CO2 emissions per tourist are still rising in many places because tourists are travelling greater distances. Due to the rising demand for tourism and increased CO2 emissions per tourist, it is critical that strategies are adopted to help slow the rise in tourism-related emissions.

Reducing that output of the greenhouse gas will require a multi-pronged approach, they said, including a reduction in transit needed to reach Yellowstone. “[T]his includes a greater proportion of local or regional visitors, fewer visitors flying, and increased fuel efficiency of vehicles,” the authors wrote.

The size of Yellowstone — 2.2 million acres — does help reduce the park’s CO2 output, which is generated by traffic as well as lodgings, museums, visitor centers, and other facilities operated by the National Park Service and concessioners, the study pointed out.

“Within the United States, the total value of vegetative carbon sequestration on National Park Service lands is $707 million annually (assuming a social cost of carbon price of $40.45 per metric ton of carbon), but there is a projected drop in future sequestration due to climate change and the increasing prevalence of forest fires,” the study pointed out. “Previous research found Yellowstone NP had the second highest carbon sequestration of NPS units and is a net carbon sink, with -1.5 megatons of CO2 annually. However, even with a substantial increase in terrestrial sequestration (i.e., land use change), terrestrial carbon sequestration alone could not offset current global emissions. Therefore, understanding and reducing total CO2 emissions remains critical.”

The study, the authors noted, was intended to spur a larger discussion around the role of tourism in generating greenhouse gases and how the outputs can be reduced.

“The work is intended to reinvigorate discussion on both the major role tourism plays in shaping the climate and the many ways tourism’s effect can be mitigated through strategic interventions, such as marketing strategies that change the composition of visitors or regulations that improve the fuel efficiency of vehicles,” they said.