There seem to be countless national park stories in the media about “best this,” or “best that,” or “most underrated” park. More often than not, those stories revolve around the 63 “national parks” that are included within the 428 units of the National Park System. What about the remaining 365 units? Let’s take a look at some of the most overlooked parks in that universe (and we hope you’ll help!).

Here’s a partial list from first-hand experience:

Valles Caldera National Preserve is a park unit with great promise/Patrick Cone photo of Valle Grande

Valles Caldera National Preserve, New Mexico

Though the National Park Service needs to complete a visitor management plan that includes access, trails, pullouts, allowed activities, and perhaps even campgrounds, this nearly 90,000-acre wooded and mountainous slash of New Mexico really is hidden. And there’s so much to see here: Human history that dates back 10,000 years; the remains of a volcanic eruption 1.25 million years ago that created the caldera; a small number of sulfuric acid springs known colorfully as Kidney and Stomach Trouble Spring, Footbath Spring, Ladies’ Bathhouse Spring, Laxitive [sic] Spring, Turkey Spring, Lemonade Spring, and Electric Spring; old-growth stands of 400-year-old Ponderosa pine; New Mexico’s largest elk herd; and blue ribbon trout streams. The Park Service can’t complete the visitor management plan soon enough…but once it does, Valles Caldera likely will pop up on every national park traveler’s must-see list.

Eight-hundred years ago, ancestral Puebloans settled in the region and grew crops, while Spanish settlers arrived in the 1500s with their sheep herds. Ranching took hold in 1860, when a land grant given to the descendants of Luis Maria Cabeza de Baca gave rise to Baca Location No. 1, a sprawling ranch that decades later was returned to the public landscape.

Nearly 200 bird species have been spotted in the preserve, which the National Audubon Society has labeled an Important Bird Area. Cross-country skiing is popular here, and the network of old logging roads hold promise for mountain bike trails.

Fort Larned is the best Civil War-era fort in the National Park System, in part due to the rocks used to build structures like the officers’ quarters/Kurt Repanshek file

Fort Larned National Historic Site, Kansas

You really need to want to reach Fort Larned in western Kansas, but if you’re interested in post-Civil War military history this is a must stop on your parks’ itinerary. Here you’ll find the best preserved Civil War-era fort in the National Park System (Fort Laramie National Historic Site is nice, but it doesn’t come close). No walls surround Fort Larned on the Kansas prairie, which makes it easy for your eyes to roam across the surrounding countryside that was home to Union soldiers from 1860 to 1878 when they were tasked with guarding travelers along the Santa Fe Trail, protecting mail routes, and negotiating with area tribes that were growing increasingly concerned with the flood of settlers.

It’s not hard to envision the physical aspects of the fort as it appeared in the 1860s. The barracks appear as they would with the troops out in the field, beds made and gear stowed. Although, with the soldiers forced to sleep side by side in bunk beds designed for four — two on the top and two on the bottom — sleep might have been hard to come by. The hospital, once housing for the 10th Cavalry, features well-spaced beds and yellow-painted flooring intended to make it easier to clean up blood.

The setting is austere, a snapshot of 19th century military life on the frontier.

Along with the ruins of a Spanish mission, Pecos National Historical Park preserves many kivas/Kurt Repanshek file

Pecos National Historical Park, New Mexico

Located just southeast of Santa Fe, the focal point for many is the Spanish mission and surrounding pueblos, which are indeed captivating and rich in history and stories. But there’s so much more. As the National Park Service puts it, the park “preserves 12,000 years of human history, including the remains of the Pecos Pueblo and many other American Indian structures, Spanish colonial missions, homesteads of the Mexican era, a section of the Santa Fe Trail, sites related to the Civil War Battle of Glorieta Pass, and a 1900s ranch.”

You cannot take all that in and do it justice in just a few hours. A full day might not even be enough if you spend time walking the grounds, climbing down into the kivas, trying to imagine how big the mission that dates to the 1600s really was at its peak. The story of the arrival of Spanish explorers and their Franciscan friars and how they subjugated the Indigenous Pecos population is particularly poignant, as is the revolt the Pecos mounted in 1680 to drive out the Spanish.

The Glorieta battle marked the end of the Confederacy’s New Mexico campaign. Their plan for the campaign was pretty straightforward. Brigadier General Henry Hopkins Sibley and his Texan volunteers would advance up the Rio Grande from El Paso to Albuquerque and Santa Fe. From there, they would move eastward along the Santa Fe Trail, crossing the mountains at Glorieta Pass, and then turn north. After seizing the supply base at Fort Union, Sibley would take the mines of Colorado while disrupting federal communications with California, Nevada, and Oregon.

Only about 4 percent of the 170 million acres of tallgrass prairie that once swept across North America remain, and you can find some at Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve/NPs file

Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve, Kansas

Tallgrass prairie? Check. Bison on the prairie? Check. Western livestock magnate? Check.

“Anyone could find Yellowstone or Yosemite, and I highly recommend it. But in my head, it takes a true believer to find your way to a place like this in the middle of Kansas, which for many people is just something you drive through on your way to a Yellowstone or Yosemite or Rocky Mountain,” Tallgrass Prairie Ranger Eric Patterson told me as we walked the grounds.

What better recommendation can you find?

The preserve embraces a remnant of North America — a fraction of the roughly 4 percent of tallgrass prairie that remains from the 170 million acres that once covered the continent. You’ll also find the mansion Stephen Jones built for his wife, Louisa, and their family that was the center of their more than 7,000-acre Springhill Farm and Stock Ranch.

The 11-room mansion he had built out of native limestone stands tall just above Kansas 177 and just below a reliable spring. It contains two parlors, Jones’ office, a dining room complete with dumbwaiter for hauling meals up from the kitchen, and three bedrooms. In the basement is a spring room that once kept perishable items in a trough flowing with cool spring water. Not far from the backdoor stands a rather elaborate outhouse, one built with limestone blocks and featuring three “seats,” including a child-sized one for the Joneses’ young daugther, Loutie.

Closer to the house is a curing building for salting meats, while across from the house stands the three-story barn, an imposing 100-foot-long by 60-foot wide structure with two ramps that lead to the second level where equipment and hay were stored. There also was a sod-roofed chicken house, complete with an adjoining “scratch shed” for the hens and roosters to roam and search through straw for grains and other foods during the winter months.

The Palmer-Epard Cabin at Homestead National Historical Park/NPS file

Homestead National Historical Park, Nebraska

While the park celebrates the Homestead Act that opened up the West to settlement, it also tells stories that reflect jubilation and anguish, deprivation and self-determination. Not only were those once enslaved persecuted and threatened in places they tried to homestead, but Native Americans who long lived on the “free land” the federal government was giving away were both displaced and, if they wanted to claim back some land through the act, had to renounce their tribal connections and apply for U.S. citizenship.

The differing views on the very existence of Native Americans on the land are explored in the park’s visitor center. While John Quincy Adams in 1802 ignored their existence — Shall the fields and the valleys, which a beneficent God has formed to teem with the life of innumerable multitudes, be condemned to everlasting barrenness? —, artist George Catlin, who traveled the plains with various tribes in the 1800s, feared for their plight — The Indians of North America were once a happy and flourishing people.

Their views, though a generation apart, highlighted part of the controversy that arose out of the Homestead Act. It is just one of the stories you’ll find in this history-rich unit of the park system.

Cape Lookout National Seashore is wonderfully free of crowds/NPS file

Cape Lookout National Seashore, North Carolina

Cape Cod and Cape Hatteras have the national seashore star power on the Eastern Seaboard, and that makes Cape Lookout even more appealing for those who know about it and have visited. No gaudy commercialism here, just a mostly wild seashore with minimal development, and that development comes largely in the form of surf caster’s shacks for rent.

Running 56 miles along the lower leg of North Carolina’s Outer Banks, this younger, and rougher, version of its older neighbor, Cape Hatteras, is not for everyone. No bridges tie Cape Lookout’s three islands (North Core Banks, South Core Banks, and Shackleford Banks) to the mainland, no paved roads are stitched through the islands, and there are no Mini-Marts to dash out to for that item you forgot to pack.

What this seashore does offer is a helping or two of the wild. There are horses running wild on Shackleford Banks, white egrets roosting in trees gnarled and twisted not by high winds or heavy snows but by salty spray, and mile-after-mile-after-mile of beaches to comb. There also has been the occasional oddity turning up on the beaches, such as a massive fossilized shark tooth and a 2-pound clam shell, also fossilized. You’ll also find some of the most amazing collection of seashells washing up here, and a fascinating community that was one of the oldest seafaring villages on the East Coast.

As I noted in 2011 after visiting Cape Lookout, the lack of paved roads, of air-conditioned rental units, of marinas bobbing with catamarans, fishing fleets, and yachts, and of seafood-dispensing shacks, is as refreshing as the sea breeze.

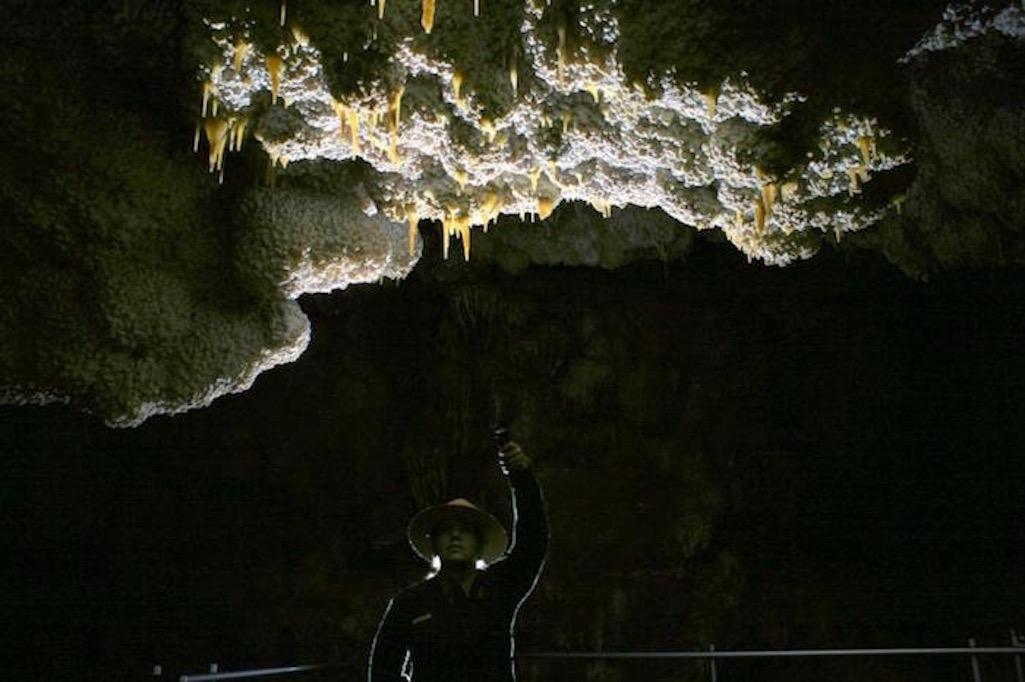

Jewel Cave is a rich subterranean treasure in the National Park System/NPS

Jewel Cave National Monument, South Dakota

Neighboring Wind Cave National Park is better known (and has its own bison herd!), but Jewel Cave is fascinating and offers some great cave tours. Along with the Scenic Tour that is offered year-round, you can journey into the cave by flickering light on the Historic Lantern Tour, or get a quick sample via the 20-minute Discovery Tour, which takes you into the Target Room.

Jewel Cave practically shimmers with the world’s greatest concentration of bright white dogtooth spar, colorful soda straws, flowstone, and cave bacon. These are the speleothems; the decorations of the underworld. They are fashioned over time by minerals deposited from water droplets dangling from ceilings, splashing to the floor, or simply carried on air currents and accumulated by chance in frost-like forms.

Brothers Frank and Albert Michaud, two local prospectors, discovered the cave in 1900. The two claimed that they stumbled across the cave entrance when they noticed wind coming out of a small opening. (Nearby Wind Cave was discovered by the same means.) Neither of the Michauds could wiggle into the cave, but they soon returned with dynamite, blasted a wider opening, and made discoveries that forever changed the course of life in this remote part of the country.

Until the late 1950s, Jewel was appreciated as “a small, but pretty cave.” Then, in the late 1950s, further exploration revealed additional lengthy passageways. By the early 1960s the world finally learned that the Jewel Cave system is astonishingly long. Today it ranks No. 5 in the world in length, with more than 219 miles mapped. During your visit, ask a ranger if Jewel Cave and Wind Cave are connected. You might be surprised by the answer.

You’ll also find above-ground trails in the park, as well as a nicely preserved cabin built by the Civilian Conservation Corps.

The John Smith Chesapeake National Historic Trail ties into many other recreational spots, such as Riverbend State Park along the Potomac River in Virginia/NPS file

Captain John Smith Chesapeake National Historic Trail, Virginia, Maryland, Delaware, New York, District of Columbia, Pennsylvania

You easily could spend a week exploring this incredible watershed. There’s paddling, sailing, fishing, crabbing, history, geocashing, interesting towns, great restaurants, and more.

Captain Smith explored the Chesapeake Bay and the rivers running into it between 1607 and 1609. The Englishman was searching for the mythical Northwest Passage that would provide a quick route to the Orient, but three years of exploration failed to find it … because it didn’t exist. But the captain did discover a place where, as he wrote in his Description of Virginia in 1612, “the mildnesse of the aire, the fertilitie of the soil and the situation of the rivers are so propitious to the nature and use of man as no place is more convenient for pleasure, profif and man”s sustanence.”

Many rivers drain into the Chesapeake, and America’s earliest colonial-era cities were situated at or above the fall line of these rivers, including Richmond, Virginia, on the James River, Fredericksburg, Virginia, on the Rappahannock, Washington, D.C., on the Potomac, and Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, on the Susquehanna. Other streams and rivers’the York, Patuxent, Nanticoke, Choptank, and Elk, to name a few, drain more than 64,000 square miles of land.

There you have it, a start to a great list of off-the-beaten-path parks. What would you add?