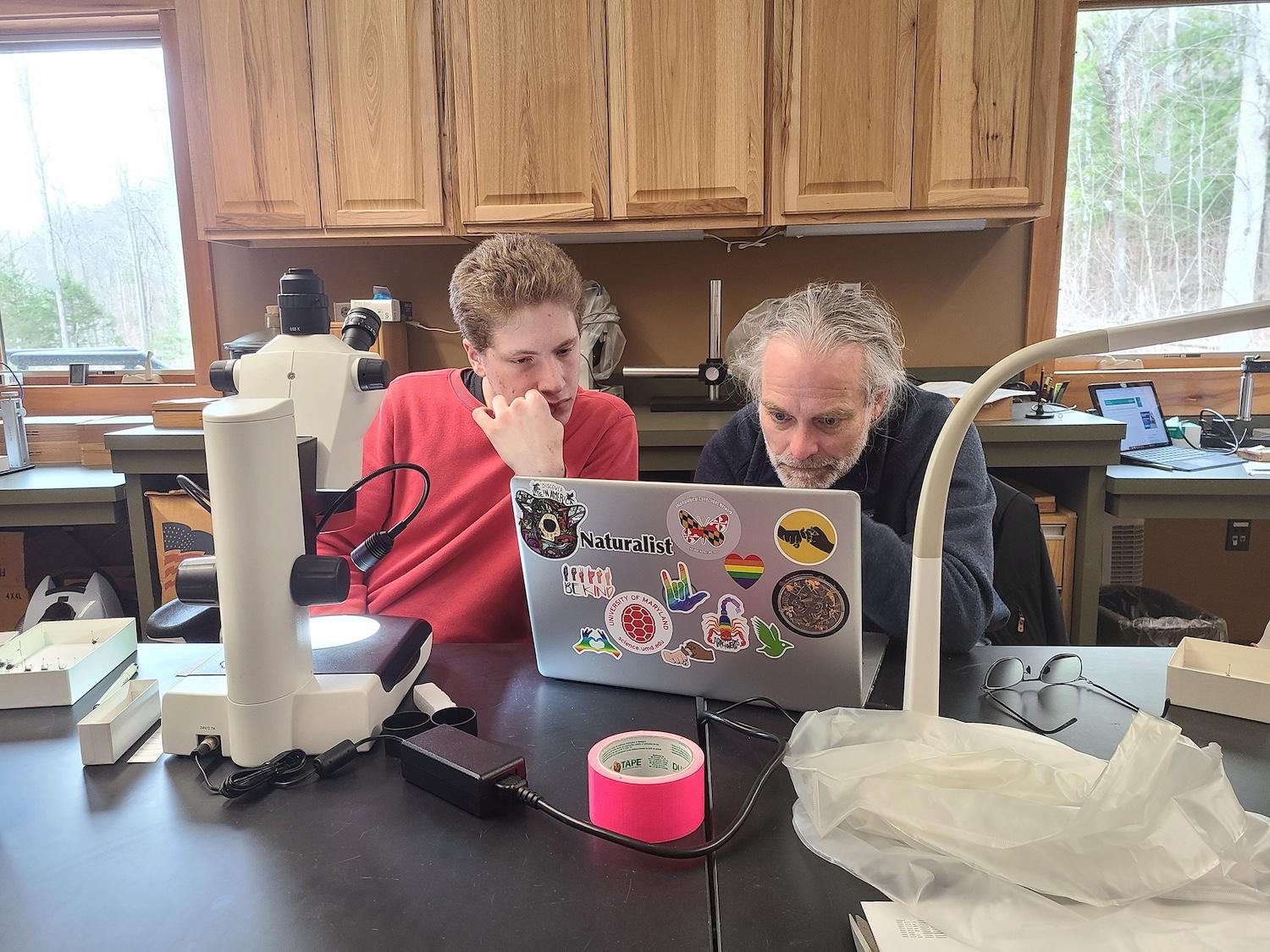

Scientists take a break from sifting through the collections at Twin Creeks Science and Education Center to capture some new specimens off the Little River Trail at Elkmont/DLiA

Fly Specialists Converge To Name Hundreds Of Smokies Specimens

By Holly Kays

Editor’s note: America’s national parks are repositories of this country’s rich natural history, and the exceptional biodiversity found in Great Smoky Mountains National Park is case in point. The park’s natural history collections are housed in the Twin Creeks Science and Education Center in Gatlinburg, Tennessee, a 15,000-square-foot LEED-certified building completed in 2007. The building contains an impressive number of insect species and includes specimens collected before the park was even established. Discover Life in America, a nonprofit partner to GSMNP, aims to identify, catalog and observe the park’s estimated 60,000-plus species through its flagship project, the All Taxa Biodiversity Inventory. As part of that goal, it’s working its way through the many unidentified specimens contained in the collection.

Two decades ago, thousands of flies, bugs, and beetles met their end in insect traps set up at 11 sites around Great Smoky Mountains National Park, part of a still-young effort to catalogue every species found within the park’s 800 square miles. From there, the insects were taken to the park’s Twin Creeks Science and Education Center, pinned, placed in drawers, and—for the most part—left untouched ever since.

That is, until last month. Discover Life in America [DLiA], which manages the All Taxa Biodiversity Inventory project to document every species that lives in the Smokies, held its first-ever Fly ID Blitz from March 1–3. Rather than roam the outdoors looking for new observations to log, as occurs in the bioblitz events DLiA often hosts, the ID Blitz brought in specialists from all over the continent to put names to the thousands of fly species contained in the collection.

“There are probably thousands of new species records for the park among this material and probably hundreds of new species to science just sitting here, languishing in this lab space,” said Will Kuhn, director of science and research for DLiA. “So we decided to bring the energy of this bioblitz concept but have it be focused on stuff that’s already been collected.”

After baffling the specialists for its stubborn nonconformity to ID keys, this fly was identified as Lepidodexia hirculus, a species previously reported only in Texas, with help from the worldwide community of fly specialists/DLiA, Will Kuhn

For two and a half days, 11 people—including Kuhn, three park employees, and seven fly specialists—spread out through two rooms in the science center, sorting through drawers of dried flies. Working a combined 131 hours, they sorted 1,500 flies to at least the family level and 500 beyond family to genus or species. Of those, 49 are likely new records for the park, equivalent to 16 percent of all new species added last year, though DLiA is still working to confirm this status. Additionally, scientists pointed out scientific literature that notes six fly species not on DLiA’s current list that have previously been documented in the Smokies.

“Even after the event,” Kuhn said, “a couple of them have been sending us other links to papers like that. … It’s the gift that keeps on giving.”

The scientists sorted themselves into two groups, with some placing the flies into taxonomic families while others concentrated on already-sorted specimens within their area of specialty, working to identify them to genus or species. At various times in the past, the park has found funding to bring an individual specialist to the park to work on the backlog, but this setup was much more enjoyable and productive, said Smokies Science Coordinator Paul Super, who has cultivated an expertise in identifying flower flies.

“Sometimes it’s just easier and more fun if you bring everybody together for a particular large group, like flies in this case.” he said.

Katja Schulz, who works as a data scientist in Washington, D.C., but has maintained a love for fly identification since completing a PhD in entomology years ago, said spending time with the other fly specialists was as big a part of the attractions as exploring the collection. In addition to the days spent at Twin Creeks, the group took a couple short hikes, ate together, and stayed at the same Airbnb. Support from Friends of the Smokies made it possible to cover travel, food, and lodging for the visiting specialists.

“When you’re a scientist, your heroes are not so much people who are in the movies or in music,” Schulz said. “You admire scientists who have done important work, and in this case, in entomology, and some of those people were at this ID Blitz.”

According to Bradley Sinclair, a fly specialist with the Canadian Food Inspection Agency and Canadian National Collection in Ottawa, Canada, wings are key to fly identification. Their distinctive vein pattern allows a trained eye to immediately discern which group of flies the specimen belongs to. From there, features like color, patterns in the hair and bristles, lobes on the body, and characteristics of the eyes and antennae offer clues to nail it down further.

“If it’s my specialty group, I can usually get it to genus on sight without a microscope or any sort of magnification, just from experience,” Sinclair said. “You use a microscope to confirm the genus, and then the features to get beyond that usually are more microscopic.”

Zachary Dankowicz and Bradley Sinclair work together to identify a perplexing Lepidodexia hirculus specimen during the Fly ID Blitz, held March 1–3 at the Twin Creeks Science and Education Center in Great Smoky Mountains National Park/DLiA

The specialists used taxonomic keys, scientific papers, books, and species checklists to help make their identifications, but they also sought help when those tools didn’t do the job.

“Folks were shouting back and forth, trying to learn from each other when they’ve got an unusual specimen they’re trying to look at,” said Super.

But identifying some specimens required an even bigger team, as was the case with a tiny fly [photo above] measuring less than half a centimeter in length.

“One of the other participants and I struggled even to get it to a family level it was so bizarre-looking,” Sinclair said.

After reaching out to colleagues scattered around the world, they were able to identify it as Lepidodexia hirculus, a species that had previously been reported only in Texas.

The scientists sought outside help for two additional finds as well. Unlike the Lepidodexia hirculus, which was part of the collection, these flies were spotted on a group hike at Chestnut Tops Trail. The first was a fly found perched on a dead snail, identified as Amoebaleria defessa, a species that had been documented in the park only seven times before. The second was a member of the Ophiomyia genus, a leafminer, found on a solitary pussytoe plant. This marked the first time a leafminer of any kind had been recorded on this species anywhere in the world.

Such finds underscore how little is known about many of the species with which we share our world—and how much remains to discover. Especially when it comes to flies.

Fly specialists peer through microscopes as they work to identify some of the thousands of fly specimens stored at the Twin Creeks Science and Education Center in Great Smoky Mountains National Park/DLiA

“Most people don’t really pay attention to them, so they’re one of the underdogs in the entomological world,” Schulz said, “one of the more diverse families but not as intensely studied as some other groups.”

Sinclair said he’s described more than 400 fly species in his career so far, but an “endless stream” of others waits to be identified.

“Even in North America, I find, when I do a study, about one-third have a name and two-thirds are unnamed,” he said.

Learning that a species exists is just the first step to unlocking the secrets of its impact on the earth. Flies are diverse in more than just looks: They play a dazzling array of roles in the ecosystems they inhabit. Flies pollinate flowers, transmit diseases, turn dead animals into rich soil, dole out painful bites, and clean dirty water, all niches that exert a powerful influence on the health of the larger environment. But for many species, humans remain ignorant of exactly what that influence is.

“Knowing which species are here is important,” Kuhn said, “so that we can better understand how these different species are connected, which species are most vulnerable, and where the hotspots for biodiversity are in the park, so that these species can be protected.”

Flies, these “underdogs of the entomological world,” help hold it all together.

“Without them,” said Super, “the whole ecosystem would fall apart.”