Landing a job with the National Park Service requires some ‘privilege,’ according to our guest writer/Rebecca Latson file

Privilege: A Required Qualification to Work with the National Park Service

By Ashley Daffron

Graduate Student in Conservation Leadership at Colorado State University

In the breakroom, grumbling with my fellow park rangers about how expensive living outside Arches National Park was, everyone shared personal information about making ends meet. We were all childless, from upper and middle-class families, and all but one of us were white. And we all had one thing in common: every one of us had financial support to meet our basic expenses—a second job, a partner with a well-paying job, or, in my case, parents who supplemented my income. Without this support, none of us would have been able to work for the National Park Service (NPS).

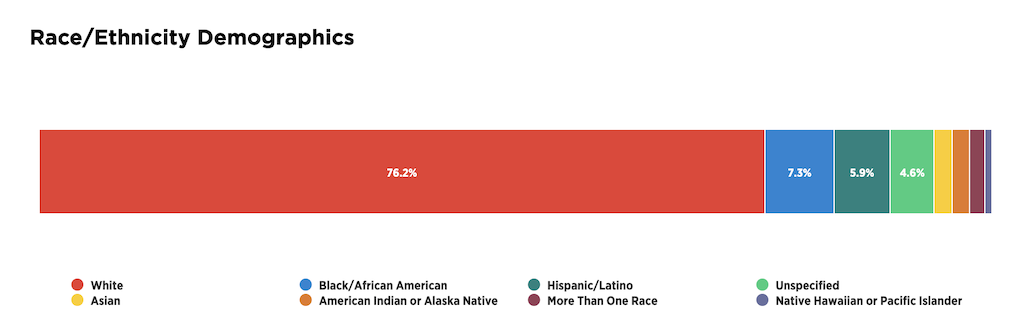

You need an incredible amount of privilege to work for the NPS. I had the right combination of privilege to snag a job as a Fee Technician at Arches National Park because I had the support and resources, the right connections, and parents who could help. For many, especially people of color, this isn’t the case. The NPS has many barriers that prevent underrepresented and underprivileged groups from entering its workforce—the current hiring structure, relocation requirements, and low-paying entry-level jobs are a few. With a staff that is over 75 percent white, it is clear that the NPS must tackle these institutional barriers to remove “privilege” from its list of required qualifications.

The National Park Service workforce is more than 75 percent white, according to the annual Best Places to Work in Federal Government survey.

The NPS’s hiring process deters certain candidates. I recently heard from a colleague that he asked current rangers for advice when he applied to work with the NPS. The top answer? Learn how to use USAJobs. Most jobs with the NPS require applicants to apply through USAJobs.gov, the federal government’s hiring website. The website is anything but user-friendly. Research on the federal hiring process describes USAJobs as challenging to navigate and notes that it doesn’t provide enough search mechanisms to help applicants discover jobs that align with their interests and skills. The study found job descriptions containing over 1,500 words, and many were “‘barely comprehensible’ to an untrained reader.”

If the applicant manages to successfully navigate USAJobs, after submitting their application, they are met with competency assessments (think SAT exams) that can take up to five hours to complete. When I took these assessments, I questioned how badly I wanted this job when one of the questions required me to make a seating chart for foreign diplomats with a complex list of rules to follow. But the real question is—who is this process really weeding out? Seen as a “learned skill, not a genuine measure of competency”, these standardized assessments are less about a candidate’s job-relevant skills and more about their ability to test well or access to the resources to do well.

If the applicant is lucky enough to land a park service job, chances are they’ll have to move to do it. For many, moving to a national park is fulfilling a bucket list item, but for others, it means leaving their community, family, support system, and even ancestral land behind. Many permanent NPS staff start their careers in seasonal positions, moving to different parks with each new position. Research has shown that for many Black adults, where they live, and their community significantly influences their self-perception. Similarly, Indigenous women are recognized as essential pillars in their communities, and moving from their communities to foreign ones is a difficult decision, one that often is not a prized choice. Within many of these underrepresented groups, community is incredibly important, and having to leave them is a significant barrier that keeps these diverse candidates out of the NPS.

National park gateway towns like Moab, Utah, can be prohibitively expensive for park staff on low salaries/Kurt Repanshek file

Many NPS positions typically require a bachelor’s degree or a few years of specialized experience, usually through underpaid internships and entry-level jobs. In my case, as an entry-level employee, I earned about $20,000 less than the livable wage in Utah. Most of my coworkers on the same pay scale, including myself, were spending almost if not a whole paycheck just on rent in Moab. Even with support from my family, this played a large part in why I left the park service after only a year. An article in High Country News described these jobs as “‘the playground of rich white kids,’ whose family support makes the low pay tolerable.” The folks who can afford to take these jobs, especially seasonal positions, get a leg up when applying for more senior or permanent positions in the agency, thereby perpetuating the privileged nature of the agency.

Privilege is the unspoken required qualification to work at the National Park Service. The NPS needs to reform its hiring process and make USAJobs more accessible to a wider audience, create better opportunities for candidates from underrepresented groups, and create entry-level positions that pay a living wage. While the agency claims it is working towards creating a more inclusive workforce, the NPS will only meet this goal once this issue of privilege is addressed.