An aerial view of Western Brook Pond, a landlocked freshwater fjord that’s one of the jewels of Gros Morne National Park in Western Newfoundland/Barrett & MacKay Photo, Newfoundland and Labrador Tourism

According to the Dictionary of Newfoundland English, a pond is a “natural body of still water of any size.” So that explains how a landlocked freshwater fjord that’s 10 miles long, 540 feet deep and surrounded by towering cliffs came to be called Western Brook Pond.

I would call it a lake. UNESCO calls it a “globally significant landscape.” Parks Canada calls it one of the crown jewels of Gros Morne National Park.

Even cloaked in fog and obscured by heavy rain, Western Brook Pond lives up to its accolades. So let’s start at the beginning, which in this case means the trailhead.

To see Western Brook Pond you must drive to a parking lot 20 minutes north of the town of Rocky Harbour, hike 45 minutes to a dock area to pick up boarding passes, take a two-hour boat trip with BonTours, and then hike another 45 minutes back to your vehicle.

Shelley Hann and Glen Laing, tour guides with BonTours, stand by the West Brook II after a trip on Western Brook Pond in Gros Morne National Park in Western Newfoundland/Jennifer Bain

That’s about four hours of effort to experience something Parks Canada says was “a billion years in the making” here in Western Newfoundland — and yet it’s one of the most popular things to do in the park.

UNESCO kicks things off with a marker explaining that Gros Morne was given World Heritage Site status for two reasons. First, its diverse rocks — like the alien orange ones I’ve just admired on the Tablelands trail — have “contributed to our understanding of plate tectonics by illustrating how an old ocean closed and mountains were formed.” Second, this “wilderness environment of landlocked, freshwater fjords and glacier-sourced coastal headlands is also an area of exceptional natural beauty.”

From the UNESCO marker, it’s a gentle 1.7-mile trek across bogs and through the forested limestone ridges of the park’s coastal lowlands. Don’t rush this part — stop, look, listen and read.

The crushed stone trail to Western Brook Pond is a work in progress that replaced a narrow footpath and boardwalk/Jennifer Bain

It’s admittedly jarring to set out on unsightly crushed stone, but this multi-use trail is a work in progress that aims to be more accessible with lower grades, an even surface and rest areas. The trail replaced a narrow footpath and boardwalk (yes there was an outcry) and promises to be more sustainable and less prone to flooding, washouts, potholes and rutting. Native trees, flowers and berries are being planted alongside it.

“In the meantime, please bear with us as we make this vision a reality,” Parks Canada implores visitors. While the trail isn’t officially wheelchair accessible, all-terrain wheelchairs can be borrowed from a shed and golf cart rides can be arranged for a fee by those with mobility issues.

Most people walk, some lingering to read interpretive signs that lay the groundwork for the big reveal. I read how the massive gorge of Western Brook Pond was carved by glaciers from the ancient rock of the Long Range Mountains, which are the most northern section of the Appalachians.

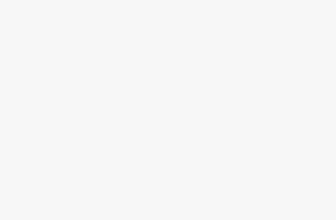

An interpretive sign along Western Brook Pond Trail explains why a ridge of limestone conglomerate is important/Jennifer Bain

Geology is doled out in digestible spurts.

The steep escarpment of the Long Range Mountains marks a crack (fault) in the Earth’s crust that was created when continents collided about 400 million years ago. The land on the far side of the fault was thrust up and over the land on the side that I’m walking on, buckling the rocks of the lowland.

During the last Ice Age, glaciers flowed off the plateau here.

“The great weight of the glaciers depressed the land, pushing the lowlands below sea level,” signage explains. “When the ice melted, sea water flooded the U-shaped valley and Western Brook Pond became a fjord. Relieved of the weight of the ice, the land rose. The emerging coastal lowland cut Western Brook fjord off from the sea. Fresh water flushed out brine, and the fjord became a spectacular 165-metre-deep lake.”

What’s called tuckamore by Newfoundlanders is spruce that has been bent and stunted by coastal winds/Jennifer Bain

I stop to admire an exposed chunk of limestone conglomerate that’s separated by layers of softer shale and formed nearly 500 million years ago at the bottom of the long-destroyed Iapetus Ocean. Hollowed out by erosion, the shale layers create wet conditions for bogs, and alternate with the dried, forested limestone ridges.

I learn that tannins color Jacob’s Pond brown because water picks up this natural material as it flows through peat and leaf litter. Sphagnum is “the boss moss here.” This sponge-like plant traps many times its own weight in water and keeps the bog cold, acidic and low in oxygen, stopping decay so dead plants pile up and the bog slowly grows higher. There is even some tuckamore, spruce trees that are bent and stunted by coastal winds.

“Close your eyes. Take a big sniff. What does this forest smell like? Resinous? Spicy? Christmas trees?” a sign instructs by the conifer-rich boreal forest. It’s black spruce, the province’s official tree, and it thrives in wet soil at the edge of the bog. Its branches are used to brew spruce beer, while the dried resin (known locally as frankum) was traditionally chewed like gum.

A moose “exclosure” along Western Brook Pond Trail prevents hungry moose from gobbling up protected patches of boreal forest/Jennifer Bain

When Western Brook Pond finally comes into view, I’m dazzled by the cliffs that surround it and rise up nearly 2,000 feet (that’s higher than the CN Tower in Toronto where I live).

In a small building by the dock, people snack on seafood chowder from a café and wait to hear if the weather will cooperate for our tour.

BonTours runs boat trips — always weather permitting — from mid-May to early October. Tickets cost $54 (cheaper for kids) and everyone needs a park entry pass to use the trail and dockside facilities. The boats hold 99 passengers.

Walking Western Brook Pond Trail, you will eventually see the landlocked freshwater fjord and the dock area where BonTours operates its boat trips/Jennifer Bain

Outside, there’s more interpretive material. Two area models show how things looked at the height of the last glaciation and how they look today. Ancient seashells found here prove this was a deep saltwater bay — a true fjord — before sea levels fell and it technically became a lake.

I don’t blame people for still calling it a fjord, and “pond” has a nice ring to it when Newfoundlanders say it.

When I look from the dock into the cold, clear, pristine water it’s too dark to see any of the Atlantic salmon, American eels, brook trout and Arctic char that live here. But I’m glad to learn that BonTours’ vessels have a special certification required by Parks Canada so they have minimal impact on the environment.

You’ll see several waterfalls in the cliffs on either side of Western Brook Pond on a boat tour of the landlocked freshwater fjord/Jennifer Bain

We climb aboard West Brook II to cruise between billion-year-old cliffs and gush over waterfalls. We see the small dock where back-country hikers are dropped off for challenging day or overnight trips to the top of the gorge. That’s what you have to do to replicate the iconic photos of hikers standing on a rock looking down on the fjord.

Given the weather — “rain at times heavy with risk of thundershowers” — I take shelter on the lower level of the boat instead of sitting on the upper deck.

“Watch the baseball caps because they tend to end up in the pond and we don’t go back for them,” teases Glen Laing before he and fellow guide Shelley Hann launch into running commentary about the pond’s historical and geological features.

Back-country hikers stand on a rock above Western Brook Pond in 2013. It’s an iconic shot that many try to replicate on day-long or even overnight hiking trips in this part of Gros Mornne National Park/Barrett & MacKay Photo, Newfoundland and Labrador Tourism

Credit goes to David Baird, the provincial geologist who was so struck by Western Brook Pond that he lobbied the premier to get federal protection for the land that would become Gros Morne National Park Reserve in 1973.

On tours, the guides always have to explain why this is called a pond — and how the boats got here.

“Since you all walked in here today, I’m sure some of you may be wondering how we got these beautiful boats in the pond,” says Laing.

The West Brook III was loaded on a sled and hauled in by tractor across the bog just south of the hiking trail in winter when the bog was frozen and covered in snow. The West Brook II — our boat — was flown in here in pieces by helicopter and reassembled in a boathouse because recent winters haven’t been cold or snowy enough. All of the materials for West Brook I were brought to the boathouse where the boat was completed.

A view from a boat tour of some of the impressive cliffs and rocks along Western Brook Pond/Jennifer Bain

The guides talk about the woodland caribou and moose that call Gros Morne home. They point out Snug Harbour where hunters, trappers and fishers once took shelter from the gale-force winds that arrive in fall. They tell us the names of multiple waterfalls — Blue Denim, Woody Pond, White Point and Pissing Mare — and regale us with the story of a 1994 rockslide that happened while the West Brook III was on the water.

“I guess I don’t have to tell you, it probably scared the living daylights out of every one of them,” says Laing. “There was a huge cloud of dust and a tremendous amount of noise.”

My favorite moment happens when we’re asked to use our imaginations and follow large cracks in one particular section of rock as they split and create a shape that looks like a large, pointed human head.

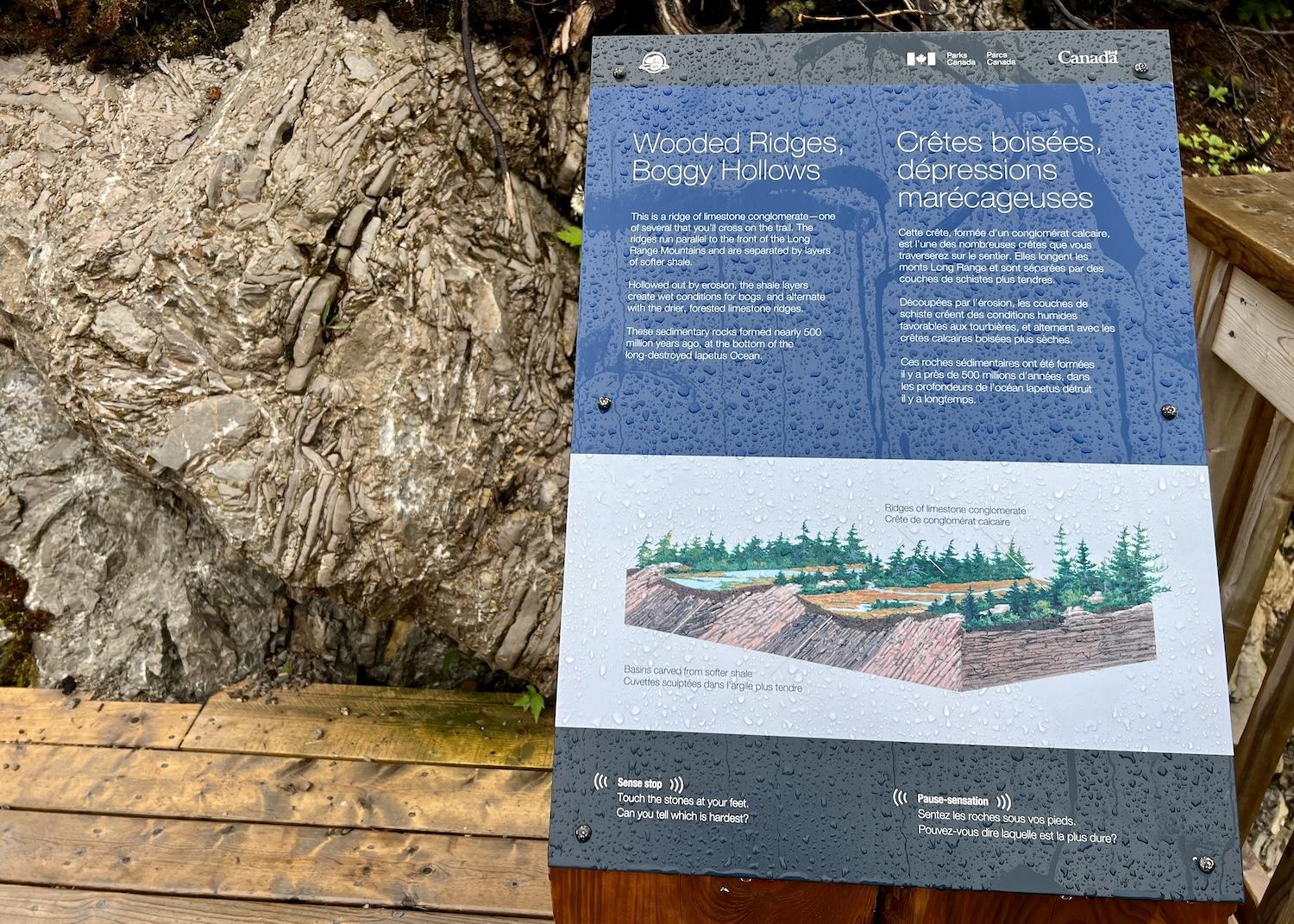

BonTours guide Glen Laing shows a laminated photo while telling passengers how to spot the “Tin Man” in the rocks along Western Brook Pond/Jennifer Bain

“He’s bald on one side with green hair, or trees, on the other. He has two sunken eyes, a piston-shaped nose, a mouth and a large extended chin,” the guides say. “Over the years we’ve had people say that this looks like a lion’s face or a tiger’s face, but here at Western Brook Pond, he is simply referred to as the Tin Man from the Wizard of Oz.”

As Laing points out, “the Tin Man is smiling right down on top of us.”

Later we do the same thing for the Old Man in the Mountain, whose silhouette appears out of another cliff. He’s easier to see with his pronounced forehead, eyebrow, eyelid, large nose, lips and chin even though he’s about 650 million years old.

BonTours takes people on boat tours from one end of Western Brook Pond to the other and then back for a two-hour journey between mid-May and early October/Jennifer Bain

The West Brook II takes us from end of the fjord to the other before turning back.

We grumble about the rain but are grateful to have dodged the gorge’s epic south-westerly winds that can stir up large swells and create breaking waves. Newfoundlanders, naturally, have a colorful name for these sheets of swirling water — water devils.

As the guides put on traditional Newfoundland music for the final, commentary-free minutes of our journey, they have one final request. “We hope that this landscape, carved by ice and lapped by the sea, will linger in your memories,” they say and everyone nods knowing that Western Brook Pond really is as advertised — a place like no other.

On a rainy day in July 2023, people wait for the signal to board a BonTours boat on Western Brook Pond for a guided tour of the landlocked freshwater fjord/Jennifer Bain