There are many like it, but finding an original Enfield Jungle Carbine takes some investigative work.

During World War II, there was a great deal of wartime improv when it came to weapons. And, among those was the invention of a curious variant of the famous British Enfield: the legendary Jungle Carbine.

A Brief history of the Jungle Carbine

The British Empire was at war all over the world by 1944, and its soldiers found themselves spread out from their home ground to the frigid battlefields of Central Europe, to Africa and the Middle East, and to the jungles of the Pacific. Commonwealth troops fought battles against the Axis powers on all fronts … and they often found themselves carrying less-than-ideal weapons.

The standard British military rifle of the era was what we call the Enfield, commonly the No.4 Mk1. The rifle was great for the time, if slightly less powerful than its American and German counterparts, and fired the .303 cartridge, typically in a 174-grain weight depending on place of manufacture. The rifle was the same general size as all the standard battle rifles of the era, not oppressive, but definitely not small.

In the latter half of 1944, a smaller, lighter Enfield-based carbine, the No.5 Mk1 and later Mk2, was developed for airborne forces deployed in Europe—not the Pacific—though the ideas behind it stemmed from jungle fighting. It would not be until the post-war years that it was dubbed the “Jungle Carbine” due to its use in the British colonies against communist forces.

Eventually, the carbine was retired from service, largely due to a condition that the British government referred to as “wandering zero,” which has since become a commonly repeated statement among military collectors. The alleged problems with the carbine stated that, at a point in a rifle’s lifespan, unpredictable to anyone, the guns simply stopped holding zero … and the British had to give up on the carbine.

The reasoning behind why the rifles mysteriously began to collectively lose zero is largely unknown, because like many people who have owned and shot these carbines over the years could tell you, that issue seemed to have resolved itself upon their import to America. Yet, we Americans have our own rumors, such as receiver stretch in Enfields—again an unqualified bit of lore that likely stems from people installing improper bolt heads, which can cause headspace issues.

At any rate, the Jungle Carbine saw limited use as compared to other Enfield variants, but real examples of this carbine have become hot commodities.

So, what are these “real” examples?

Fake It ’Til You Make It

Supply has a way of running out before demand can be filled when it comes to military collectibles. See, the collector market never knows when a given type of gun will suddenly take off in popularity, and sometimes the values go through the roof due to that demand. Likely because regimes lacked foresight that collectors would want the weapons they used to oppress and destroy their neighbors, world militaries stopped making certain versions of their guns before enough had been made to fill enthusiast demand.

Due to the failure of government, various enterprising salesmen and importers began trying to replicate these popular models themselves, and there is likely no more faked military rifle than the Jungle Carbine.

True examples of this carbine, like the one featured in this article, are very rare. This particular one is completely original and was “won” off a British soldier. It was a “bringback” and has no import markings, and I have verification from the seller that this rifle, and story, are as original as it gets.

A carbine like this can go for as much as $1,800 if it bears all the proper features. This rifle is in good shape, but I’ve seen better as in regard to overall condition. As you can imagine, with such a popular and distinct profile, there’s money to be made if one were to get creative with a supply of existing full-size Enfield rifles.

And that’s exactly what happened.

The odds of finding a completely original Jungle Carbine are slim. There was only about 250,000 made, and after spending a great deal of time on research, I came to some conclusions:

- 1. A large number of the real-deal carbines were left in British colonial territories and used by local and government forces in various small-scale conflicts through the next 80 years, most eventually lost to time and circumstance.

- 2. Roughly 10,000 of these guns might have made it to the United States between 1946 and 1960, but it’s impossible to determine how many remained in colonial service.

- 3. Many were destroyed or had receivers replaced to remedy the wandering zero issue.

- 4. More still were disregarded as original due to local-level alterations, such as installing a standard Enfield stock, replacing handguards, and removing or replacing the conical flash hiders.

With originals so few, it comes with an easy understanding that these guns were simply faked for the American market. The vast majority of Jungle Carbines stateside are copies, at an estimated 20:1 ratio—or higher. Importers were given a fairly wide range of options in the post-war era, and many types of guns were assembled here in the States after quantities of leftover parts were bought as surplus. One primary importer created all the confusion: Golden State Arms/Santa Fe. This company is responsible for altering countless Enfield rifles.

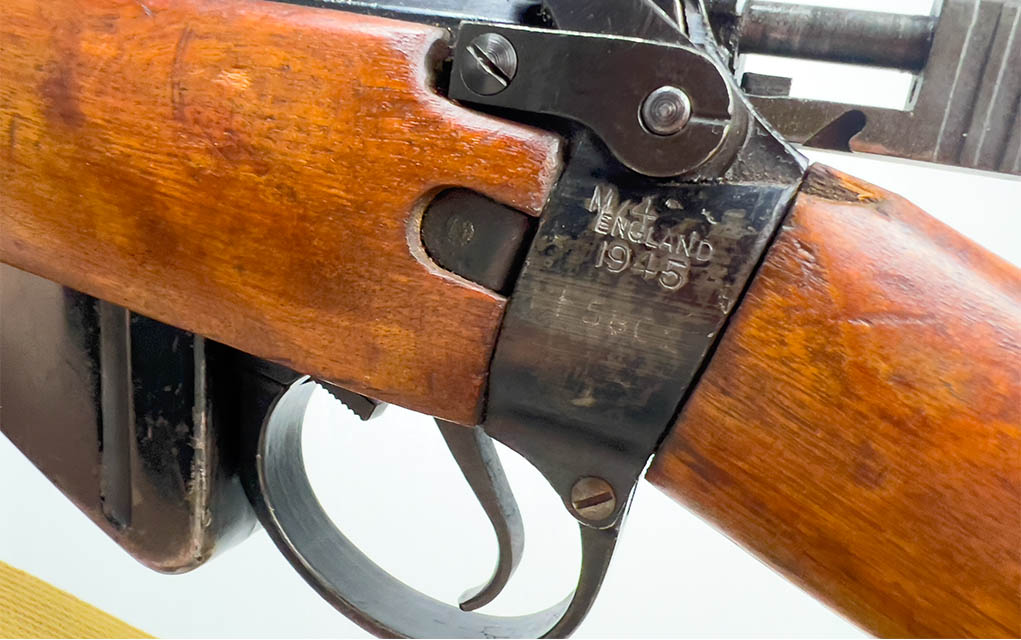

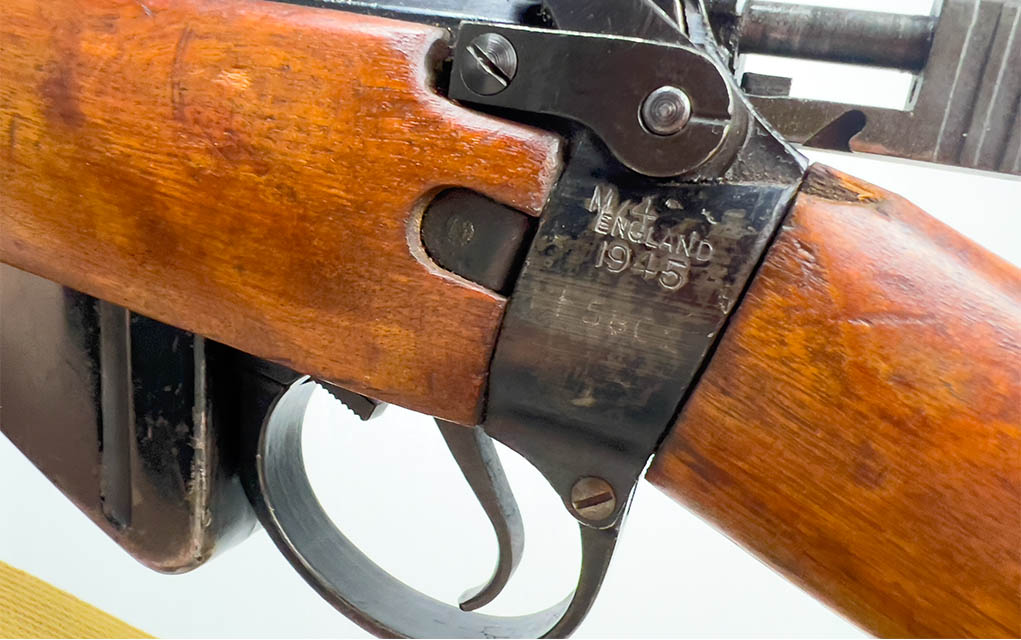

The main thing you must look for on a fake is the markings. If it has solid receiver stamping, or has any “US PROPERTY” or actual British model markings, it’s a fake. No manufacturer on this side of the Atlantic, or any other British factory except BSA and Fazakerly, made true No.5 carbines … and they didn’t stamp them with a model number. The Brits were in an understandable hurry and literally stenciled “No.5 Mk1/2” on the side of the receiver, or nothing at all. The visible stamping on the receiver wrist should read ENGLAND, and a year.

Another telltale feature for identifying an original is one often hidden: Under the handguard, the barrel has deep flutes cut around the chamber area. This was a standard model feature for the No. 5 and is virtually non-existent on fakes, unless they use an original barrel, which is possible. No versions of this gun were ever made in .308/7.62 caliber at the Ishapore factory, yet I’ve seen a hefty share of “Ishapore Jungle Carbines” over the years. If you see that, know immediately that it’s a fake. The only correct chambering for a No.5 is .303 British.

The stock is also an interesting point of inspection on these guns. I’ve rarely seen a fake that did away with the No.5 buttplate; it’s such a distinctive part of the gun that it’s usually added to make it more convincing. Brass buttplates common to other Enfield variants are incorrect even as a replacement, but it isn’t hard to get a correct version should you find an otherwise original carbine.

Curiously, the stock grip’s endcap is a heated point of discussion. True No.5 carbines can have either a metal endcap or a sporter-style rounded endcap. If you have a metal endcap, you can be sure it’s a real stock, but of note is that some field-repaired real-deal carbines will lack the cap. This is still a point up for debate among collectors: I fall into the camp that maintains a rifle should be totally original to be considered a true original because, if we let that detail slip, what’s to say that we start letting other details slip due to what may have been a one-off repair job?

The rear sight of these guns is known to vary a bit on originals. Early rifles had elevation adjustments out to 1,300 yards, and later on models, the sight was altered max out at 800, as shown on the rifle in this article. Both are technically correct for the Mk1 carbine, so don’t get too caught up on this detail. That said, all Mk2 carbines should have the reduced-range sight, as is the case on my carbine here.

There isn’t much ado about the front sight/flash hider assembly. True examples will have a bayonet lug, and be on the lookout for any that lack this, as they are incorrect.

How to Find a Real Jungle Carbine

I’d love to share some special knowledge I have on exactly how to find these, but there is no magic. I bought this particular rifle at a local gun shop. I will say that gun shows are not the best place to go if you want an original. If you want an altered rifle, or just one to have fun with, be my guest and demand a price less than $500. The minute a military rifle is sporterized, it loses all general value, and don’t be convinced to pay more for a chopped-up Frankenstein.

For your best bet on locating that needle in a haystack, pay attention to specialty gun stores that deal in military surplus, or surprisingly, your local Class 3 dealer. Guys who deal in machine guns are often tight with military collectors. It’s helpful to leave a note explaining that you aren’t looking for a knockoff, and give them this list: Stenciled No.5 marking/no marking on receiver, .303 chamber, ENGLAND wrist stamping, milled flutes under the handguard, painted/enamel finish, stock endcap, and 1300/800 yard rear sight.

These are the minor details you’ll want, and the rest you can visually determine, like the correct buttplate and bayonet lug. These guns do pop up from time to time, with a realistic price ranging from $800 for a beat-up example to $1,800 for perfect specimen. So you can compare, mine, as in the gun featured in the images in this article, would likely sell at $1,000-1,500 … depending on the demand at the time.

Editor’s Note: This article originally appeared in the June 2024 issue of Gun Digest the Magazine.

More Classic Military Guns:

Next Step: Get your FREE Printable Target Pack

Enhance your shooting precision with our 62 MOA Targets, perfect for rifles and handguns. Crafted in collaboration with Storm Tactical for accuracy and versatility.

Subscribe to the Gun Digest email newsletter and get your downloadable target pack sent straight to your inbox. Stay updated with the latest firearms info in the industry.