The outdoor portion of African Burial Ground National Monument in Manhattan includes the Ancestral Chamber and the Ancestral Reinterment Ground/Jennifer Bain

For all those who were lost

For all those who were stolen

For all those who were left behind

For all those who were not forgotten

***

In a sacred sliver of outdoor space near City Hall in Lower Manhattan, those four sentences are etched onto a 24-foot-tall green granite monument alongside a heart-shaped Sankofa, a Ghanian symbol that means “learn from the past to prepare for the future.”

The dramatic memorial forces us to acknowledge the role that enslaved Africans played in building New York City. It’s a shameful story that might have been forgotten had workers building a federal office tower in 1991 not unearthed human remains 24 feet below the street.

Each of the seven mounds at the Ancestral Reinterment Ground holds a crypt that in turn holds about 60 hand-carved wooden coffins/Jennifer Bain

All told, 419 human skeletal remains were exhumed, studied and eventually reinterred after a public outcry. That’s only a fraction of the estimated 15,000 enslaved and free Africans that were laid to rest between the mid-1600s and 1795 in a cemetery here that once spanned 6.6 acres or what’s now five city blocks.

The rediscovery sparked a grassroots movement to protect this hallowed ground and tell this important story. In 1993, 0.34 acres of the cemetery became the first below-ground New York City landmark and a national historic landmark. On Feb. 27, 2006, the African Burial Ground National Monument was proclaimed by President George W. Bush.

“Do you know why you just had to go through that airport-style security — put all your stuff through the X-ray machine and go through the metal detector?” ranger Bethany Burnett asked when I joined two other people for a public orientation tour in January. “This is a federal office building. So, I know it’s hard for people to picture when we’re in this museum, but on the other side of the wall, there’s an office building that houses the IRS, FBI, EPA and federal courts.”

When the Ted Weiss Federal Building was being constructed in Manhattan in 1991, an African burial ground was found 24 feet beneath street level.

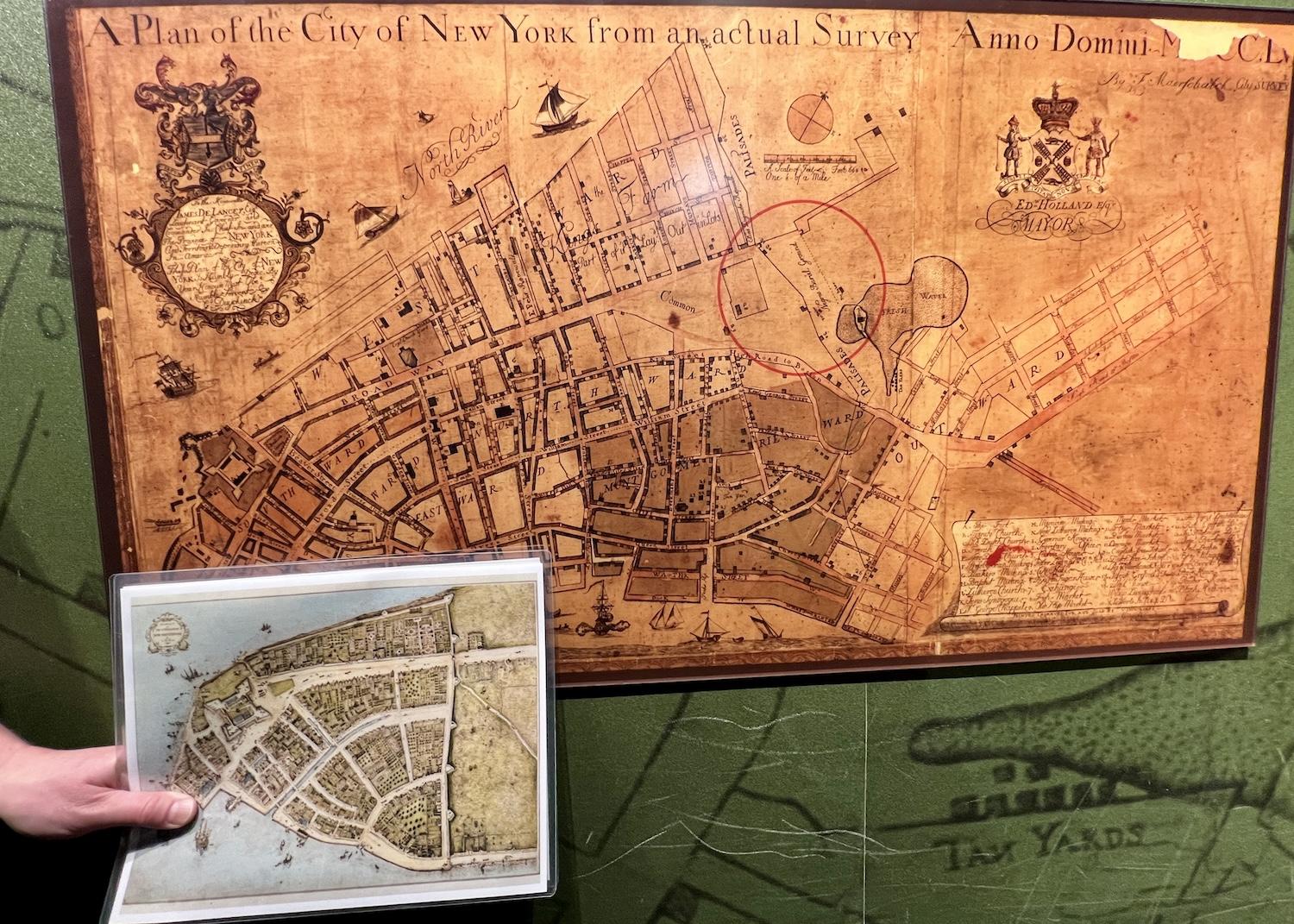

This National Park Service unit — one of 12 surrounding the port of New York City — is divided over two separate spaces. The outdoor memorial is at African Burial Ground Way and Duane Street. The visitor center is around the corner on the ground floor of the Ted Weiss Federal Building at 290 Broadway and has its own entrance.

During the 30-minute tour, Burnett brought the sobering story of slavery to life.

“This is the oldest and largest non-excavated burial ground in North America for free and enslaved Africans,” she said to begin. “Its rediscovery in 1991 really changed how we talk about the history of New York. Often when we talk about slavery, we’re focusing on the south or we’re focusing on plantations or we talk about the Caribbean. Often we don’t talk about slavery in northern urban areas like New York itself, and yet the rediscovery of this burial ground really showed the prevalence of slavery in norther urban centers like New York.”

In the African Burial Ground National Monument visitor center, you will learn about urban slavery and funeral restrictions/Jennifer Bain

Africans were captured and brought to the Dutch colony of New Amsterdam on slave ships from different regions with diverse cultures, religions and languages. In 1664, the British took over New Amsterdam and renamed it New York.

Before the American Revolution, the NPS says, New York had more enslaved Africans than any other colony in the north. Along with free Africans, they were forced into manual labor. Men cleared farmland, filled swamps and built structures and roads. Women sewed, cooked, harvested and cared for their owners’ children as well as their own. Children carried water and firewood.

These enslaved people usually died of physical strain, malnutrition, punishment and diseases like yellow fever and smallpox instead of old age. But they were buried with dignity and respect.

Ranger Bethany Burnett shows a 1798 image of how Manhattan looked when it was a hilly wilderness with a large lake/Jennifer Bain

It’s hard to imagine now, but this concrete jungle was once hilly wilderness with a 50-acre freshwater lake called Collect Pond. Burnett shared a laminated photo of a 1798 watercolor that shows why the Lenape people who lived here before anyone else used the name “Island of Many Hills.”

Colonial laws banned African burials in officially consecrated graveyards. They prohibited large gatherings of enslaved Africans and decreed that funerals must be held in daylight between the end of the work day and sunset.

Here, on the tip of the island and outside what was once a slave-built wooden wall, Africans created a cemetery on undesirable sloped land near a ravine. As the city expanded, the burial ground was closed and the land was divided into lots and sold. Buildings went up. The lake became polluted and was drained and filled in.

“For almost two centuries, New York City’s growth obscured the graves, and the African Burial Ground was nearly forgotten,” interpretive signage points out.

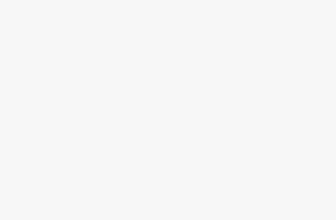

A 1755 map shows the “Negros Buriel Ground” circled in red. The smaller picture shows how what’s now the tip of Manhattan Island was protected by a wall. The African Burial Ground was outside that wall/Jennifer Bain

Fast forward to 1991 and the U.S. General Services Administration (GSA) had plans for a 34-storey office building. Archaeologists did a cultural resource survey and studied older maps to figure out what might be destroyed or displaced. On a 1755 map — called the Maerschalk Plan — they saw the “Negros Buriel (sic) Ground.”

“So an important point here is that the federal government knew there was a burial ground here prior to beginning work on this building,” Burnett told us. “They knew they would be unearthing human remains but chose to proceed with construction anyway. Archaeologists assumed that because this burial ground closed down in 1795 and the city continued to build on top of — and around — the burial ground, that most of the burials would have been destroyed by more recent construction. And so they thought maybe they would find about 30 sets of intact remains.”

Between 1991 and 1992, the remains of 419 individuals were unearthed and it became clear that this was a sacred site. While there were laws in place to protect Native American burial grounds, there were none to protect Africans from desecration.

“Understandably, people were really upset because here these remains were being removed with no plan in place for how to respect and care for them, in part because nobody expected so many,” said Burnett. “And so a lot of people became involved in activism — the descendent community, local politicians, leaders in the clergy, anthropologists, archaeologists, the general public.”

The African Burial Ground National Monument has its own entrance in the Ted Weiss Federal Building, but also has airport-style security since rangers can take tour groups through a locked door into the building lobby/Jennifer Bain

This activism led to several compromises. After the remains were carefully studied at Howard University’s Cobb Biological Anthropology Laboratory, they were reinterred in a 2003 ceremony at what became the outdoor memorial space. The tower went up but now showcases relevant artwork in the lobby and includes a 2010 visitor center.

The interactive center is open Tuesday to Saturday from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. There are special events throughout the year, but especially in February for Black History Month. Daily tours are free but there’s a $1 fee if you go book through Recreation.gov.

After going through security, I watched a 21-minute film called Our Time At Last about how African labor helped shape the Americas and how the African Burial Ground was rediscovered.

“In the end, this is not Black history, this is American history,” David Paterson, the first African-American governor of New York, concluded in the film. “But it’s American history that has finally been told.”

The showpiece of the African Burial Ground National Monument is this life-sized recreation of a 1754 funeral that’s also depicted in a short film/Jennifer Bain

The film recreates the funeeral of a man and young girl, pointedly with 14 mourners, two more than laws at the time allowed.

Stepping out of the theater, you’ll see a life-sized scene with three women and two men gathering at dusk to lay two loved ones to rest in 1754. The women were lifecast from the film’s actresses while the men were male models. “It’s the same wax as Madame Tussauds,” Burnett revealed. The simple wooden caskets were film props.

On a nearby wall is a map with color-coded coffins — green for men, purple for children, gold for women and blue for undetermined. More than 40 per cent of the burials were children, but since most of the cemetery remains buried under other buildings, nobody knows if this sample of 419 people is indicative of the whole area.

You can touch a handmade coffin from Ghana in the African Burial Ground National Monument visitor center/Jennifer Bain

Burnett also showed us a hand-carved, infant-sized coffin commissioned from Ghana and lined with hand-woven Kente cloth. It was an extra coffin and never held human remains, she said, “so that way you can actually see and touch and experience what the coffins were like to reinter the remains.”

Many of the people laid to rest in the African Burial Ground were lovingly wrapped in shrouds. Pennies were placed over their eyes to keep them closed. Small artifacts — like beads, shells and cuff links — were sometimes buried with them. You can see replicas of some of these treasured objects.

“Unfortunately, despite the importance of this burial ground and the hugely important contributions of the individuals who used this space, we don’t know much about these individuals,” Burnett lamented. “We don’t know the names of these individuals. We don’t know any of their oral histories.”

Each set of remains was given a burial number in the order that it was archived.

The NPS protects just a fraction of the space within the estimated historical boundary of the African Burial Ground in Lower Manhattan/Jennifer Bain

One man — Burial #101 — is featured both here and in the artwork in the lobby. He was buried in an unusual fashion with iron tacks arranged on his coffin lid in the shape of a heart or, more likely, a Sankofa symbol.

“You start wondering, who was this man, what role did he play in his community, why is he buried in such a fashion, was he born here, was he born in Africa?” Burnett said. “His teeth were filed, which is a traditional African practice, so he may have been born in Africa. But regardless, this Sankofa symbol has become symbolic of this burial ground.”

With that, she led us through a locked back door in the visitor center into the lobby of the Ted Weiss Federal Building for a second half-hour tour, this time devoted to art.

Ranger Bethany Burnett stands by a sculpture called Africa Rising in the Ted Weiss Federal Building lobby. She shows photos of accomplished African Americans who are featured on coins at the base of Barbara Chase-Riboud’s bronze/Jennifer

We saw several pieces, starting with a dramatic bronze sculpture called Africa Rising by Barbara Chase-Riboud that shows a woman with two faces who is likely on a slave ship and is looking back to Africa and towards the New World. Scatterd along the base are coins featuring people of African descent who achieved great success.

I was struck by Unearthed by forensic sculptor Frank Bender. This “uncommonly talented” artist was allowed to interact with the precious human remains to reconstruct what people may have looked like. He picked three for his bronze sculpture. In a time when the average age of death was 22.3 years, one woman lived to 50 or 60 and became Burial #89.

“I held the eldest woman’s skull in my hands and felt that she had endured the most,” Pender said in an artist’s statement. A younger woman (Burial #25) had been shot with a musket. A man, the youngest and tallest of the three, is Burial #101 and is shown behind the women “rising for the hope-filled future.” The hands of this trio are joined to show the artist’s “belief that we are all one in death,” said Burnett. “You’re welcome to lay your hands over theirs.”

In the Fred Weiss Federal Building lobby, Unearthed by Frank Bender shows what he imagines three people look like whose remains were unearthed at what is now the African Burial Ground National Monument/Jennifer Bain

Weather permitting, the rangers lead tours of the outdoor memorial. But it was closed that day as snow melted and the pavement became slippery.

Three days later, on a rainy day as temperatures climbed, I returned to complete my exploration of what’s considered one of America’s most significant archaeological finds of the 20th century. I got to explore the Ancestral Libation Chamber, designed by Rodney Leon when he was with AARIS Architects and featuring seven elements.

This time I knew that the eye-catching Ancestral Chamber is 24-feet tall to represent how deep below the pavement the exhumed remains were found. The four-sentence dedication is on what’s called the Wall of Remembrance.

A four-sentence inscription, and a Sankofa image, are etched into the Wall of Remembrance on one side of the Ancestral Chamber at the outdoor memorial of the African Burial Ground National Monument/Jennifer Bain

The interior of the chamber apparently recalls a ship’s hold and is a place for contemplation and prayer, but it has been closed since August 2022 because it’s showing signs of stress and must be reassessed. I was able to wander through the Circle of the Diaspora, a circular wall, spiral processional ramp and interior court below street level that displays cultural and spiritual images from the African diaspora.

What was most sobering, however, was the Ancestral Reinterment Ground. It’s roped off and lies in front of a large Sankofa symbol in one of the Ted Weiss building windows. There’s a grove of seven trees (bare in winter) and a grassy area where you can just make out seven mounds.

Each mound contains a large African mahogany crypt and each crypt holds about 60 of those hand-carved wooden coffins from Ghana. Everything was made with tongue and groove joints, rather than metal components, to eventually return to the earth. It was here, on Oct. 4, 2003, that the exhumed ancestral remains of those 419 people were reburied, as close as possible to the original positions with heads facing west.

The Ancestral Chamber, a place for contemplation and prayer, is closed due to safety concerns. It is showing signs of stress and must be reassessed/Jennifer Bain

Flowers, two per person, are welcome. I found a tiny pot that held a pink flower and a white one. The sacred ceremonial ritual of libation, with a liquid offering, can also happen here with a permit.

Nearly 24,000 people visited the outdoor memorial last year, while almost 17,000 entered the visitor center. The ranger wasn’t with me when I returned but I thought about how she prepared for her public tours by reading books and watching movies. She relayed something an unknown man said in one of those films, something powerful that has stayed with her.

“What he said was, `If I could go back in time and talk to any of the individuals who used this space and who were buried here, I wouldn’t ask them about the conditions that they faced because I’m sure that that was horrific. Instead, what I would ask them is, in all that happened to you, and in all that continued to happen to you, what did you hope for and what did you tell your children?’”

People are welcome to leave flowers at the African Burial Ground National Monument outdoor memorial, but only a maximum of two per person/Jennifer Bain