Hello, shooters! Welcome to AmmoLand’s five-part series on reloading. You’re not a reloader, you say? Hopefully, after this series, you will want to join the club. There’s even a secret handshake… well, not really, but we are a brother/sisterhood of sorts. Reloading has grown by leaps and bounds, even in the last decade, and has attracted many new practitioners. But why would you want to reload? And, if you answer that satisfactorily and decide to give it a go, how would you go about it? That’s what we’re going to look at in this introductory article.

Why Reload?

My typical short answer when I get that question is, why not? If you are a shooter who puts a lot of lead downrange and doesn’t just talk about shooting, you could benefit from reloading.

Three Reasons

There are three main reasons folks stand behind a loading press, cranking out round after round. I call them the “Three Cs”: control, convenience, and cost.

Control

The first one is control. You have total control over the cartridges you produce. Many wildcat rounds were started after custom dies and bullets were acquired, cases altered, and loading press handles worked up and down a lot. Even if you’re not striving to invent the next .247 Nuclear Varmint Vaporizer cartridge, you may want to take up reloading to make a load that you can’t find in a store. This is an obvious use of the customization advantages reloading can provide. You have complete control over your final product.

Convenience

I don’t know how many times I went to my reloading set-up to load five rounds of a new “recipe” that I wanted to try. Typically, this would’ve been a .45 ACP load for a 1911 that wasn’t exactly the best shooter. I’d load a few and shoot them, then go back in and load a few more with a different powder, powder charge, bullet, or whatever. I could immediately change my loads to experiment with, to find something that was at least marginally accurate in that gun. It helps that I could load five, walk out of my pole barn garage, set up on my shooting bench behind it, and let fly. I am blessed to have a 100-yard range in my (very!) rural backyard.

But, even if you need to go to a range, you can load five of this, five of that, five of the other and record your results for later quantity loading. You have the convenience of being able to do that without spending beaucoup bucks on boxes of factory ammo.

Cost

The third reason is probably more recognized than the other two, and that reason is cost. From the first day you buy reloading equipment and components (we’ll look at those in a bit), you will start to amortize the costs involved by churning out hundreds of rounds of loaded ammo. What if you don’t need that much ammo, but you’ve gone ahead and made it anyway? Hang on to it. You can’t legally sell it, but you might be able to use it to barter with your shooting buddies. That’s an option.

In terms of selling it, unless you want to apply to be an ammunition manufacturer with all the attendant costs and red tape, don’t even think about it. Not only is there the Federal bureaucratic end of things, but liability rears its ugly head. Do you want to be responsible if one of your handloads blows up a gun or, worse, causes injury? Don’t go there. Just shoot your reloads and put some away for a rainy day.

Another thing to consider is loading for your buddies by having them buy the things you need and then putting the rounds together for them. Or… they can help. More than one shooter looking over my shoulder as “we” made ammo for him was turned into a free-standing reloader just by watching how it’s done. Lower ammo costs can be a driving force behind the decision to reload, no matter what you do with your loaded ammo.

How?

OK. We’ve looked at reasons for the “why reload” part of this little article… now, we’ll examine “how.” Just exactly what do you need to start reloading? We’ll look at the reloading process and equipment first, then components.

The Process

To be succinct, reloading metallic cartridges (not shotshells… those are different and will NOT be covered here) involves this sequence of actions to be performed:

- Resize the case

- Decap the case (knock the spent primer out)

- Re-prime the case

- Flare the case mouth (only for most handgun and a few rifle calibers)

- Drop a pre-measured amount of powder into the case

- Insert and seat a bullet

- Crimp the bullet

Inspect the round for a protruding primer or other glitch. Typically, resizing the case also will decap it as the resizing die contains a pin to do that. Also, sometimes you will seat and crimp the bullet in one operation, but not always. You have that option. That’s the basic process. The process described above concerns reloading commercial, Boxer-primed cases, not military cases that might have the primer crimped into place. We won’t get into that here.

Components

To reload, you must have components. These consist of:

- Cases

- Bullets

- Primers

- Powder

Cases

Cases you should already have. You should hang on to your cases even if you don’t reload (yet)… someone else could use them. You can reload all centerfire (not rimfire) calibers, although some are easier to load than others. Calibers that we tend to reload a lot are 9mm, .223, .308, .45ACP, 380, and similar ones. These are easily loaded. Just save your cases and you won’t have to buy them. Please remember that those 7.62×39 steel cases are technically reloadable (I’ve done it), but they’re steel. Don’t waste your time or risk damaging a die. They will rust before you can use them.

Bullets

Bullets are easily obtained. I just ordered 500 .223 bullets for a reasonable amount. If you are shooting revolver or pistol calibers, you can shoot cast lead bullets. I’ve been into bullet casting almost as long as I’ve reloaded. If you load those, you can save a lot of money. That’s a different article, though. You might be better off just buying rifle-caliber bullets — they tend to be accurate, available, and as mentioned, not too expensive for the common calibers.

Primers

Primers are not as inexpensive as they once were, but neither is a Big Mac. They come in four varieties: large and small pistol and rifle, and large and small magnum pistol and rifle. For most uses, regular pistol or rifle primers work just fine. Sometimes buying them by the thousand will save you a bit of money. Also, know that Fiocchi packages their primers 150 instead of 100, in the package. I like that.

Live Inventory Price Checker

Powder

Powder is perhaps the hardest thing to come by as of this writing. I was fortunate that I had put some back over the years. (Powder lasts a long time but it doesn’t like heat — stick yours in an outdoor fridge or freezer in the summer). I also lucked into some military pull-down powder for the .223. Powders vary by burning rate… just check your reloading manual for what powders work best for your caliber.

Live Inventory Price Checker

Reloading Equipment

If you’ve never reloaded or known someone who has, you might be surprised at the world of equipment that’s out there. Reloading is, in itself, a hobby like shooting. Let’s take a look at reloading from a gadget point of view… here is the breakdown. Please understand that each of these categories has many sub-categories. For this introductory article, I won’t delve into great detail… I want you to understand what your overall options are. Here are the categories of equipment needed to reload:

- Loading Press

- Dies

- Reloading Scale

- Powder Measurement and Dropping

- Case Cleaning and Trimming

Loading Presses

You have options, for sure, with all reloading equipment, but probably none so many as with this category. Reloading presses come in four basic versions.

Hand Press

A hand press would be something akin to this Lee Precision Breech Lock Hand Press.

This press is hand-held and therefore suitable to take to the range with you. Add a portable reloading scale (such as the digital RCBS Pocket Scale for thirty-five bucks) and a way to measure and drop powder into the case and you’re good to go in terms of customizing loads on the spot.

Single-Stage Press

This press performs one function at a time, hence its name. You screw in one die and perform that operation on all your cases, then move to the next die. It takes a while, but eventually, you’ll produce finished ammo. Here’s what a modern single-stage press looks like:

The above-pictured Forster Products Co-Ax Single-Stage Reloading Press is one of the newest versions of the old standby single-stage press. It does not show the powder measure that could be installed on the side. My single-stage press is an almost 50-year-old RCBS Jr. It is well-worn and has loaded thousands of rounds. It works the same way as the Iron Press… screw in a die at the top, perform that die’s action on all your cases, then change dies and repeat until finished.

The above press has some additions that my old one could use, such as the storage on top for case mouth de-burrers, brushes, etc. These presses are known for their strength. Some cartridges, like the .50 BMG, need the strength of a large, non-flexing single-stage press. The type is still viable. But what if you wanted to speed up the process a bit? Then you might buy one of these…

Turret Press

The turret press gets its name from the rotating “turret” on top that holds the dies. Here is a Lee Precision Classic Turret Press:

This setup reminds me a lot of my own. I have a Lee turret press like this one mounted next to my old RCBS single-stage on my bench. Notice the four-station turret at the top, where you can add a resizing, case mouth expanding, and bullet seating/crimping die. The case mouth expanding die can screw into the powder measure, and it sits under the powder measure. The measure is activated by a collar on that die. It works when a case is run up into it presses the collar against the powder measure’s actuator, and releases the powder. This set-up is the same for the progressive press.

The turret press is like having three or four single-stage presses set up (depending on the number of stations it has three or four). You do not need to change any dies out… rotate the turret to the next die and leave the case in the shell holder.

A turret speeds the reloading process up, but how could you speed it up even more? By going to a true progressive press.

Progressive Press

I was recently blessed by Dillon Precision with one of their XL 750 progressive reloading presses for a couple of reviews. It looks like this:

A true progressive press can be a total game-changer for reloading. I had used all three types of presses shown above, but it wasn’t until the XL750 arrived that my reloading took wings to use an old phrase.

The main difference between turret and progressive presses is that a turret requires four handle pulls to produce a finished cartridge, while a progressive (once all stations are loaded) requires only one pull. Every pull of the handle drops a loaded round into the bin. I had always heard about the prodigious amounts of ammo that a progressive could produce in a short time. That was proven to me when I first started learning the ropes of making ammo on the Dillon. I was truly impressed with its production capability. Plus, I had a lot of loaded 9mm to prove it!

The advantages of a progressive press are obvious. Speed and number of loaded rounds in a short time make the switch worthwhile if you are someone who shoots a lot. You can easily produce upwards of 500 rounds or more an hour.

But… these presses are not cheap. And, they are complex when compared to single-station or turret presses and require much setting up to use them. When I first started using the 750, I felt like the guy on the old Ed Sullivan show who spun plates on long sticks. He had to keep all the plates spinning and in the air. His attention was required everywhere at once, rotating the sticks to keep the plates spinning. (OK, that’s a reference that only older shooters will get, but that’s what I am!). The gist of the story is: you need to watch all of the stations, plus priming and powder dispensing, all the time, every time you operate the handle.

Here’s a tip: when you operate the 750 (or other progressive press’s) handle, make sure to move it all the way up and down until it stops on each stroke. I didn’t understand that in the beginning, and I had problems.

What about changing calibers? It’s not as simple as unscrewing dies and replacing the shell holder like it is with the other types of presses. You will need a conversion kit. I was recently sent a conversion kit in .223 to review elsewhere… it took my engineer son and me a good while to get it going. Thank goodness for the instructional videos out there! If you do this regularly, it’s not a big deal but for first-timers, it was a bit involved. You will read, in part two of this series, about the ammo we produce with that .223 conversion kit and how it was done.

Dies

To accomplish the reloading process mentioned above, you will need a die set.

Most rifle die sets are made up of two dies… a resizer/decapper and a bullet seater/crimper. As I said above, you may want to invest in a separate crimp die or at least perform that operation independently to have more control over it.

Handgun die sets are usually made up of three dies: resizer/decapper, case mouth flaring, and bullet seater/crimper. Typically, revolvers will utilize a roll crimp and semi-autos, a taper crimp. Some semi-auto caliber sets come with a fourth, taper-crimp die. If yours doesn’t have one, you can buy a separate taper-crimp die if you so desire. Taper-crimping is important for cartridges that headspace on the case mouth – most semi-autos do this. Revolvers tend to headspace on the case rim, so a roll crimp works just fine.

The first die’s function is pretty obvious – you need to resize and decap the case. The reason for the second die, the case mouth flare die, is to expand the case mouth a bit to allow a bullet to be started in the case without crumpling the neck of the case or shaving lead from the bullet. It just eases the process a bit.

You can buy dies at both ends of the price spectrum. I’ve always had good luck with Lee Precision’s dies at the shallow end of the die dollar pool, while others swear by companies like Redding (shown above) or another brand that tends to swim in the diving-board end of the cost pool. The point is, whatever your budget or shooting purpose, you should be able to find dies to use without too much trouble. When COVID was rampant, nobody seemed to have any reloading supplies or equipment but that’s better now.

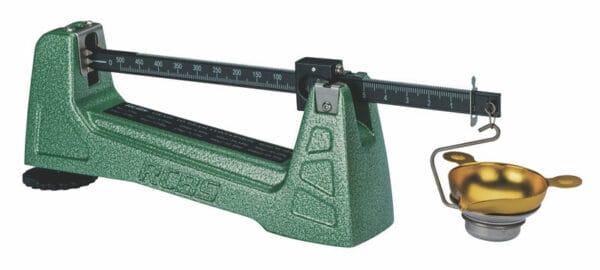

Reloading Scales

You must weigh powder charges, bullets, cases, etc. So, you will need a reloading scale of some sort. Please note that this is NOT optional! Safety requires it. There are three basic types of reloading scales. We have mechanical balance-beam scales that are truly old-school but work just fine. Then, there are what I call digital scales. These scales weigh the powder charge digitally and are faster than mechanical ones but do not dispense powder. That is reserved for the final group, precision scales. These will dispense (trickle) powder into a pan, weighing it as it falls. When it reaches the preset weight, it stops. You then dump the pan into the prepped case. Here are representative images of all three types…

You can’t go wrong with any of these or similar scales. I found that the RCBS MatchMaster (bottom) was the overall winner in terms of accuracy and speed. It uses two tubes… one for standard loads, and the other (smaller) for precise match loads. You can spend anywhere from about $40 to around $900 on a scale… you have to figure out what would work best for you. A quick tip: buy the best scale you can afford. It will be worth it.

Powder Handling And Measurement

The top tier of reloading scales (precision) will drop powder, but they won’t load powder into the case — you must dump each load into each case. If you are loading for a long-distance competition or an expensive hunting trip, you should do that. But what if you just want plinking, shoot-mud-puddles-and-tin-cans ammo?

Get a powder measure. These contraptions hold the powder in a reservoir and meter it when the actuating arm is triggered. This can happen by the action of the reloading press, like in the XL750 example above, or by you working a small handle on the measure’s rotor to drop the pre-measured powder charge. (That’s why you need an accurate scale — you need to be able to set your powder measure, and it will take a lot of experimenting and weighing to do this). Here are the two types of measures. Remember that they both do the same thing — they drop a measured charge into the case. It’s how they do that that can vary.

Here is a free-standing, operator-actuated measure: RCBS Uniflow

Now, here’s a press-actuated one: Dillon Precision Powder Measure

A forerunner of the top measure, the Uni-Flow by RCBS, has been on my reloading bench since 1978, and it’s still going strong. The second one is a Dillon Precision measure similar to what’s on my XL750 press. Notice the complexity of the second measure. This one is designed to drop a powder charge into every case (once it’s been set up) by simply operating the press handle. The top one is operator-actuated… you, the operator, have to work the little handle up and down to drop powder. They are both adjusted similarly but differ as to how they drop powder. A powder measure is a necessary component if you want speed.

But what if you don’t want (or can’t afford) a powder measure? Can you still reload? Of course! Order one of these:

This is the 15-dipper set by Lee Precision. For $16, you can get this set of graduated dippers and a reloading chart that translates grain charges into ccs. Just about all loads can be loaded with these. I have used them, and they work. Heck, I’ve even made powder dippers by cutting cases down and twisting a wire around them as a handle. .38 Special cases excel at this usage. They can be very consistent. Just remember to press the scoop straight down into the powder and fill it that way. Do not drag it through the powder, as it can compress it and put too much in the case. Yessirree, they work. That’s how I started before I could afford a powder measure.

Case Cleaning and Trimming

These are procedures that many reloaders do not perform with any regularity. Clean cases are not exactly required, but a clean case will not grunge up your dies — plus, they look nicer. Trimming applies mostly to rifle cases, although I’ve trimmed many a .44 Magnum case since they tend to stretch (as do rifle cases) with firing. Speaking of the big .44, another use for a case trimmer is to make .44 Special brass from Magnum cases. I’ve done that, too. That takes some Armstrong power — I don’t have an electric trimmer!

Rifle cases benefit from being one uniform length for all — it can aid accuracy. Reloading is all about consistency. The more consistent your loads are, the greater their accuracy potential. So, keep cases trimmed to a consistent length to have all cartridges fit the case’s overall length figure. Semi-auto cases will tend to feed better too, if they’re of uniform length. So, how do we clean and trim cases – tumblers and trimmers, of course!

Tumblers

There are a few types of tumblers, I tend to use vibratory tumblers, while others (especially those who wet-tumble) might use the rotary ones. But, for this article, I will mention and show a sample vibratory tumbler, in this case, from Frankford Arsenal.

There are a ton of tumblers out there… Harbor Freight is a good place to look for one locally. All you need to do is to buy a tumbler and some good tumbling media — that’s available from any number of firearms-related websites, or in stores like Academy Sports, Cabela’s, etc. A shiny case is a good case!

Trimmers

As for trimmers, this one is from Redding but many companies make them. If you are energy-challenged like I am (read: lazy), you can get an electric trimmer, as I mentioned above, that has no handle to crank. To trim a case, you install the correct case mouth pilot — several are included with most trimmers — and then adjust the travel of the arbor to the correct case length. Some experimentation will help you find that. Once found, lock it in and crank away! When you’re done, take a deburring tool…

… and chamfer the inside and outside of the case mouth. It’s easier to do than to talk about.

Reloading Manual

One final piece of equipment that I need to mention that is extremely important is a reloading manual. Do not put your trust in loads that you see on the internet. Just because it’s on the interweb does not automatically make it true! You can go to reloading sites such as Hornady and download info about loads. It doesn’t hurt, however, to own a reloading manual (or two). Most have loads of info past reloading data that will help you.

But… they need to be current. I have an RCBS/Speer manual I bought in 1978. It’s a museum piece. I don’t use it anymore because the info is outdated. Please buy a brand-new manual from one of the major players, and you’ll be happy.

In Conclusion

We have covered an awful lot in this first part of our reloading series… hopefully, the following articles will not need to be so involved. I hope I didn’t confuse you. Here’s the takeaway: reloading is not alchemy/rocket science/brain surgery… pick one. Reloading is not difficult and needn’t be overly expensive. But reloading does require your full, undivided attention. Reloading is a practical, decades-old method of obtaining more ammo to shoot or customized cartridges that you can’t get anywhere else.

So… why not check it out? Here’s a thought: there are many starter reloading kits on the market that include everything you need to get going. This article will give you a place to start. My only advice about these kits is, if they include a balance beam scale, to opt for a digital one. The time you save will more than makeup for the extra cost.

About Mike Hardesty

With experience spanning over 45 years, Mike Hardesty has long enjoyed shooting and reloading. An inveterate reloader, he casts bullets and reloads for a diverse array of firearms, each handled with long-practiced precision. Living in rural Indiana, his homestead boasts a personal 100-yard range where he shares his love for guns to his four sons, their wives, and eleven grandchildren. As a recognized author, his writings have been featured in notable platforms like Sniper Country, Bear Creek Arsenal Blog, Pew Pew Tactical, TTAG, Dillon Precision’s Blue Press, and Gun Made, revealing his ongoing passion for firearms at the age of 72.

Some of the links on this page are affiliate links, meaning at no additional cost to you, Ammoland will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase.